Inspiration

The screenplay is based on the 1959 novel written by Robert Bloch (who sold the screen rights for a measly $9000). Bloch’s book was inspired by the real-life story of Ed Gein, the reclusive Plainfield, Wisconsin farmer whose curiosity about human anatomy turned into necrophilia, murder, and cannibalism. This lurid tale also provided the source material for movies as diverse as Silence of The Lambs and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Bloch was fascinated by the relationship between Gein and his domineering mother, who cast a long shadow across her son’s psyche from her death in 1945 to his arrest in 1957.

Adaptation

When making Psycho, Hitchcock deliberately tapped into a cheap, exploitative aesthetic – reminiscent of the early noir thrillers churned out on Poverty Row back in the 1940s – rather than the Technicolor gloss and glamor of his previous pics Vertigo(1958) and North by Northwest (1959). Despite his stature as a leading film director, who could command A-list talent on big-budget features, he shot in black and white, within the constraints of an $800,000 price tag, using the crew from his television show on a set on the Universal backlot. Total production time was around nine months.

Hitchcock had free rein on this small-scale low-risk production and was able to make some bold and innovative choices. He structured the narrative in a way that deliberately defied expectations, developing Marion Crane’s character and story as though it was the main plot, only to kill her off after 40 minutes.

Despite her truncated screen time, Marion is one of the most memorable female characters from this era: beyond her angelic blonde appearance – and the sympathy Janet Leigh ensures we feel for her – she’s a Bad Girl to the bone. She’s introduced in the throes of a secret affair with a previously married man, a relationship that defies (as do so many other elements of Psycho) the Production Code. Marion’s prepared to sacrifice everything for this relationship and she betrays everyone else in her life by running off with $40,000 stolen from a real estate client.

This could be a solid set-up for a thriller, but a severe storm forces the narrative, along with Marion, off the planned route. She winds up as the only guest at the Bates Motel, unaware of how far from the path she has strayed. She’s driven the narrative thus far, but she’s about to give up all her power to her unassuming host, Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins). To begin with, he’s timid, stuttering, clearly in awe of her beauty and agency. However, beneath this Mama’s boy’s fragile-looking exterior beats the black heart of a psychopath, of the kind that cannot bear to see a woman doing her own thing – especially if that woman demonstrates kindness towards him.

Within Norman’s worldview, free-floating women like Marion must be punished, reduced, frozen in place like one of his taxidermied exhibits, taking up no more space than he allows through his arrangement of her withered limbs. The true horror of Psycho – the horror that still disturbs audiences decades later – comes from the sheer power of Norman’s misogynistic rage. This rage is so potent that it breaks away from him, manifesting as a separate, controlling identity that will stop at nothing – a true monster. This monster is all the more terrifying because Marion – and the audience – are unaware of its existence until it’s too late.

‘Mother’ (and we all have one) is the monster within, the stabbing, hate-driven harpy who bubbles deep within our bile tracts. Most people manage to suppress her and live out their lives without her warped maternal instincts ever rising to the surface. But Norman can’t. He doesn’t understand her, can’t connect with her, fails to acknowledge the true nature of her existence. Sitting atop his failing family business as the new highway takes traffic away from him, he resonates as a charged symbol of thwarted white masculinity unable to accept its feminine elements.

As always, Hitchcock expresses the dramatic tension spatially as well as emotionally. Norman is (mostly) himself when he’s in the motel but Mother takes over once he climbs the hill and enters his family home. Equally, there’s a stark visual contrast between the nondescript 20th-century motel buildings and the Gothic monstrosity looming behind them. Although it’s not inhabited by a ghost in the usual sense, the Bates Mansion is a classic haunted house. When Norman walks inside he’s trapped by all the named and unnamed trauma of his past. He can’t escape it because it’s the only home, the only identity he can currently see or has ever known: Mother and the mansion towering above him, dominating his psyche. He’s fully co-dependent, hence his efforts to prevent both the dusty Victorian pile and the desiccated corpse from crumbling. Within dialogue too, Mother and the Mansion are inextricably intertwined. As he explains to Marion, he can’t leave because “Who would look after her? The fire in her fireplace would go out. It would be cold and damp up there like a grave. If you love somebody, you wouldn’t leave them even if they treat you badly

The set has certainly become iconic as a building that embodies menace. It was inspired by Edward Hopper’s 1925 painting, The House By The Railroad, and was originally a two-sided facade built on the Universal lot. It still stands there, impervious to the

There are many layers to the horror in Psycho, but ultimately the power of the narrative flows from the central, seminal character. Anthony Perkins’ performance is pitch-perfect, nailing the underlying wrongness of Norman from our first sight He looks right, with his hands stuck in his pockets, peeking shyly at Janet, apologizing for the motel’s shortcomings, but there’s always something askew about his smile, a current of unease swirling beneath his hospitable affirmations. He represents a new kind of monster, one that populates many horror films throughout the 1960s and beyond. He’s the man lurking behind a mask we can’t see is a mask: he doesn’t

Reception

Hitchcock deferred any salary on the film and instead opted for 60% ownership of the negative – financiers and distributors, Paramount, took the remainder. This proved to be one of the great all-time deals in movie-making, with Hitchcock enjoying a massive payday as a result.

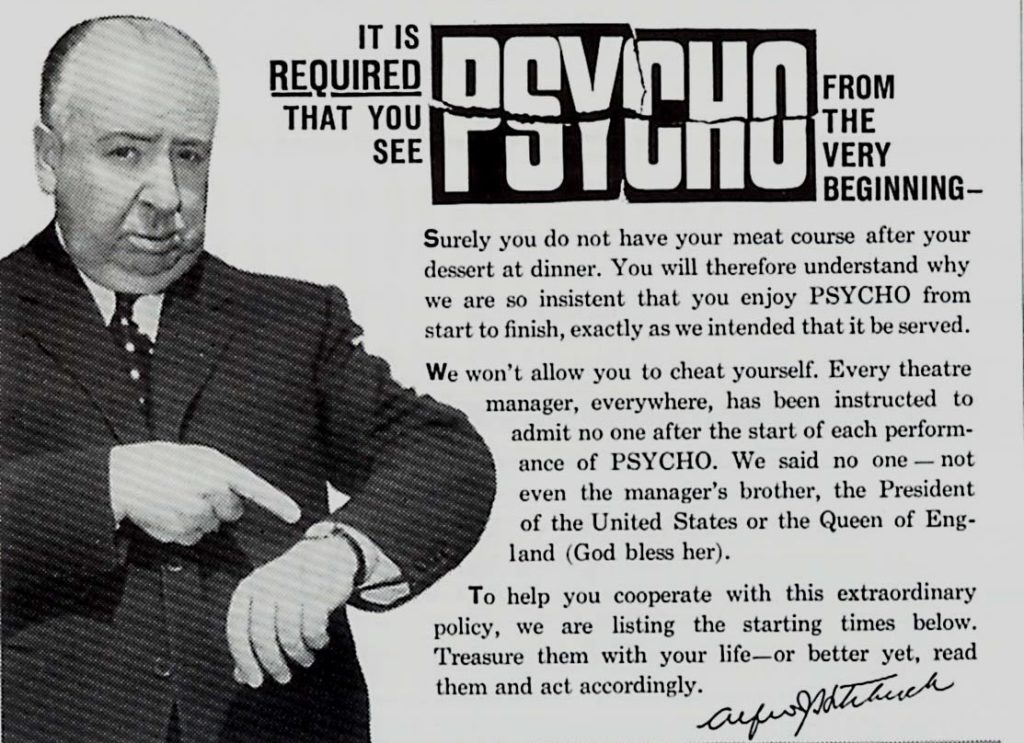

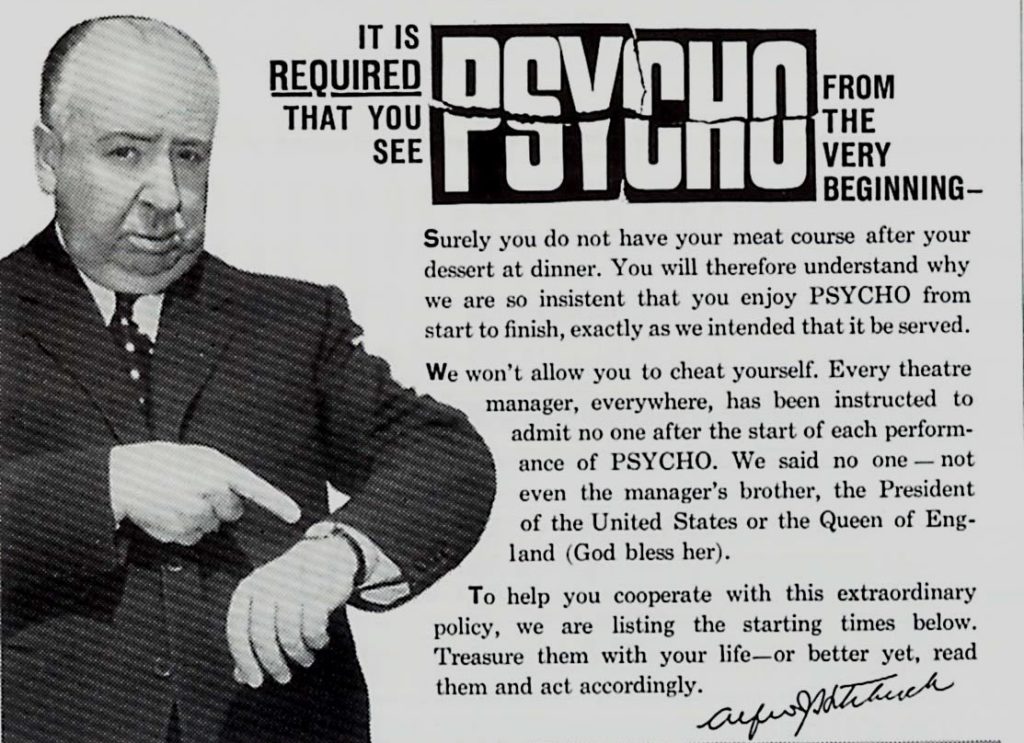

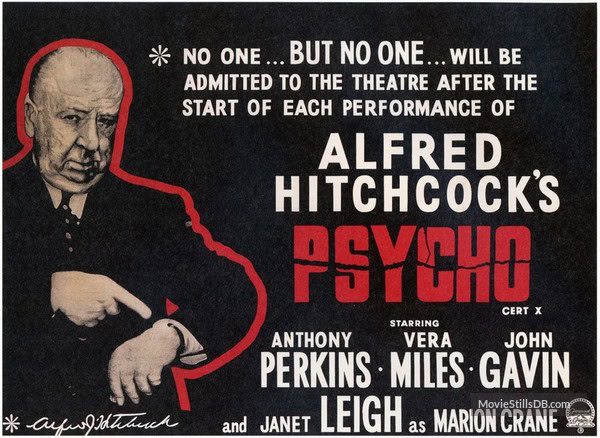

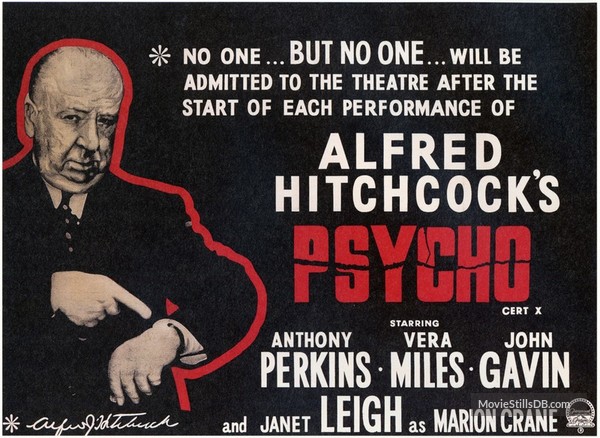

Hitchcock was famously controlling on set and in the editing room, but Psycho gave him the opportunity to demonstrate his command of the final, and often most unpredictable, part of the moviemaking process, distribution

Decades before anything went viral online, he created a storm with his campaign forbidding audience members to enter once the movie had started, and exhorting them to secrecy once it was done.

Audiences loved it, flocking to theaters – which often had a nurse staged outside sell-out houses, to cart away anyone who couldn’t cope with the shower scene. Hitchcock later told Francois Truffaut that Psycho, from start to finish, was an experiment in manipulating an audience:

“I was directing the viewers. You might say I was playing them like an organ… My main satisfaction is that the film had an effect on the audiences, and I consider that very important. I don’t care about the subject matter; I don’t care about the acting; but I do care about the pieces of film and the photography and the sound-track and all the technical ingredients that made the audiences scream . . . They were aroused by pure film.”

— Hitchcock by François Truffaut (Simon and Schuster, 1967) p.211

Iteration

Although Anthony Perkins resisted a return to the role that made him a household name (and ensured he was forever typecast) he eventually embraced his relationship with Norman (and Mother). After Hitchcock’s death, Perkins made a trio of sequels. In Psycho II(1983) he returns as Norman, who has been released after 22 years in an asylum. He heads back to the Bates Motel and history repeats itself with Meg Tilly in the victim role. Three years later, Perkins once again starred as Norman but directed himself in Psycho III, which picks up shortly after the ending of the second installment and offers more insight into the Bates family history. 1990’s Psycho IV: The Beginning (directed by Mick Garris) functions as a prequel, with father-to-be Norman reminiscing about the past as he ponders what to do about his potentially psychopathic offspring. In 1998, Gus Van Sant decided to make a color, shot-for-shot remake starring Vince Vaughn as Norman and Anne Heche as Marion. His reasons for doing this remain unclear.

In 2013, Psycho spawned a TV show, Bates Motel, which takes place in the present while functioning as a prequel. It explores the nuances of the slow (it ran for five seasons) trainwreck of the deeply dysfunctional relationship between young Norman (Freddie Highmore) and his mother, Norma (Vera Farmiga). The show, anchored by two excellent lead performances, fills in the gaps about Norman’s history, showing how the nice young man inherent in Perkins’ original depiction came to harbor such a terrible secret within.

Further Reading

- Hitchcock by François Truffaut (Revised Edition, Simon & Schuster 1985)

- A Touch of Psycho? Welles’s Influence on Hitchcock – John W. Hall, Bright Lights Film Journal, September 10, 1995

- Here’s Lookin’ at You, Kid! Alfred Hitchcock and Psycho – Alan Vanneman, Bright Lights Film Journal, April 1, 2000

- FilmSite.org – detailed review

- Cutting The Flow: Thinking Psycho – Bill Schaffer in Senses of Cinema

- Sound In Psycho —FilmSound.org