On This Page

B-Movie Babylon

1950s horror movies contrast radically with their 1940s predecessors. Understandably – they were reflecting a whole new world. It’s hard to grasp the changes that took place in popular consciousness between 1940 and 1950. The Second World War left over 40 million dead and millions more exposed to the full intensity of man’s inhumanity to man. Homecoming soldiers and bereaved widows had lived through too much personal horror to be frightened by hokey fantasies about costumed monsters in Mittel-European villages of a bygone age. The era of horror movies framed in fairy tale mise en scène was over.

1950s audiences wanted stories that connected directly to their lives, to the ever-expanding technology in their homes and workplaces. They also wanted horror movies that played to their fears – stoked by politicians – of the shadows that lay beyond their immediate, personal experience of the shiny American Dream. So, the dawning of post-war posterity in the United States brought with it a new breed of monsters, adapted for survival in North American swamps, deserts, small towns, and suburban homes.

The horror films of the 1950s are usually situated in the present day and many of them riff on contemporary technology run riot. They offer a different escape hatch to the horror films of the 1930s – they play, often to comic effect, with people’s fears about scientific developments (or disasters) taking over their lives. In many ways, it must have felt as though the mad scientists had won and were now in control.

The first thing these triumphant scientists did was start another conflict, the Cold War, a technological race toward mutually assured destruction – and guaranteed work and funding for scientists of every stripe, including the former Nazis poached by the USSR and USA (under the auspices of Operation Paperclip). The lessons learned from WW2 were clear: no matter how heroic your men, how skilled your generals, how staunch your supporters on the Home Front, at the end of the day it was technology that counted. Bigger. Better. Deadlier. The more advanced the technology, the more powerful and secure the nation.

It wasn’t just human technology that triggered collective anxiety. The first recorded sighting of a flying saucer occurred June 24, 1947, followed almost immediately by the crash of a supposed weather balloon in Roswell, New Mexico, that fueled rumors about a captive alien ship (and an autopsied alien) for decades. During the War, people had been conditioned to ‘Watch The Skies’ for enemy bombers. In peacetime, alien craft represented the next best threat.

The 1950s was also the era when horror films slid slowly and surely into the B-movie category, ignored by stars and awards shows. On the whole (and unless their studio contract compelled them) established talent opted for the paychecks associated with glossy epics, melodramas, and musicals. Up-and-comers chose to demonstrate their chops on the psychological and stylistic challenges of film noir, which quickly became the low-budget auteur’s go-to genre.

The people who made horror movies in the 1950s were those who’d always take a trip to the carnival over a night at the ballet: the showpeople, misfits, freaks, queers, mavericks, rogues, and hasbeens, anyone who felt bypassed or rejected by the mainstream. Perpetual outsiders, they relished outlandish scenarios in which smug normality gets ripped apart by an invader – the more grotesque the better. In Tarantula (1955), the eponymous house-sized spider terrorizes an Arizona desert community; in The Blob (1958), a couple of small towns are destroyed by the goo from inside a newly-arrived meteorite; Attack of the Giant Leeches (1959) pits human-sized bloodsuckers against the local Everglades townsfolk.

So did their adolescent audience, whose commitment to moviegoing ensured that genre pics still brought in a decent box office return. Teens flocked to the drive-ins in hordes, not caring too much about character development, plot integrity or production values. Instead, they wanted action, thrills, romance, tentacles, slime, and as much exposed flesh as the censors would permit. Low-budget mini-studios, like American International Pictures, saw an opportunity to make a fast buck and delivered to order. While some of the movies that proved popular with this crowd haven’t aged well, others remain highly entertaining. Across the board, they provide a glorious snapshot of the way the USA desperately didn’t want itself to be.

Creature Features

Thanks to the 1952 Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson Supreme Court ruling, films were recategorized as free speech under the First Amendment. This meant that the Production Code lost the worst of its bite and filmmakers were able to let their imaginations run riot, violating (and ridiculing) the laws of nature. As special effects and trick photography became more sophisticated, filmmakers became much bolder about the monsters they wanted to show onscreen.

The Creatures of Creature Features aren’t evil, just animals in the wrong place at the wrong time, trying to survive. They never talk although they are capable of showing emotion – and like their granddaddy, King Kong, they often have an eye for the ladies. They’re provoked into their destructive rampages by a foolish human (often of a crazed scientific bent) disobeying the rules of nature. It takes an all-American hero to marry scientific principles with common sense and decency to find a way to bring them down. It’s a shame the Baby Boomers – the postwar generation who formed the main audience for these movies – didn’t take much notice of the dire warnings about messing with the environment that many of these movies contained.

The easiest way to make a Creature was to take an existing species and make it seem strange or unfamiliar – in line with Freud’s theory of The Uncanny. Radiation (or other unspecified scientific processes, usually involving “rays”) could enlarge (Godzilla, Them!, Attack of the 50 Foot Woman) or shrink (The Fly, The Incredible Shrinking Man) them. Tiny insects could be transformed into gigantic monsters using blue- or green-screen techniques to show them interacting with tiny human actors. Alternatively, models and stop-motion animation were used to bring creatures to life. Otherwise, the old standby of a man in a rubber suit (The Creature From The Black Lagoon) could be made to work.

Ray Harryhausen was the star practitioner of stop-motion and animated effects of this era. His work can be seen in a wide range of films, from the skeleton soldiers of The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) and Jason & the Argonauts (1963), to the mutant octopus attacking San Francisco in It Came From Beneath The Sea (1955).

As a young boy growing up in Los Angeles, Harryhausen was entranced by the stop-motion effects in King Kong (1933). He poured all his energies into learning how to be an animator, taking extra classes in anatomy and art direction at USC while he was still in high school. After a stint in the Army Motion Picture Unit during the war, learning the craft of filmmaking from Frank Capra, he returned to Hollywood. His first big production was The Mighty Joe Young (1949), a giant gorilla pic from the King Kong team. Harryhausen’s meticulous stop-motion work won an Academy Award.

The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953)

The box office success of Harryhausen’s next project, The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms is credited for inspiring the slew of Creature Features that followed – including Gojira in Japan. The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms is based on a Ray Bradbury short story (The Foghorn) and centers on the accidental awakening (by atomic testing) of a long-dormant carnivorous dinosaur (a rhedosaurus) that has been frozen for millennia in the Arctic. The Beast heads south for New York, its former hunting ground, stomping on everything in its path. It can’t be killed by conventional means as its blood, if spilled, contains an ancient virus that will wipe out the human race. The only way to destroy it is to employ another type of atomic weapon.

The producer, Jack Dietz was a Monogram veteran (he produced Bela Lugosi’s mad scientist pictures for the studio in the early 1940s) and well versed in how to make a low budget shocker. He originally wanted the Beast to be a man in a suit. However, when Harryhausen found out about the project (Harryhausen and Bradbury were good friends) he talked him into stop-motion special effects.

This gave the Beast a unique quality – like Kong before him, the Beast had facial expressions, suggesting an emotional response to the puny humans who first woke him from hibernation and then hunted him to the death. No man in a monster suit with a fixed-expression rubber mask was ever able to replicate quite this level of character nuance. Audiences – as they did with King Kong – were able to sympathize with the giant reptile, whose only fault was being in the wrong place at the wrong time, and find the ending tragic, rather than a triumph of science. The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms was one of the top-grossing movies of 1953 ($5 million from a budget of $250,000) and encouraged the studios to invest in further monster pics.

Creature From The Black Lagoon (1954)

Jack Arnold directed several dynamic sci-fi monster pics for Universal-International in the 1950s: It Came from Outer Space (1953), Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), Tarantula (1955), and The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957). They were all shot in black-and-white, but It… and Creature… utilized an early 3D process as a gimmick to bring monsters directly into the theatre (although many audiences still saw the movies in 2D).

The Creature is “only” a man in a rubber suit, but the suit itself is an elaborate and expressive construction that evolved through several iterations (studio head Edward Muhl wanted it to look like the Oscar statue) and ended up costing $15,000. Bud Westmore and Jack Kevan of the Universal make up department molded the rubber suit while artist Millicent Patrick designed the mask. Two versions of the suit were made, one for Ricou Browning to swim in, and one for the (much taller) ex-Marine Ben Chapman to wear during the ground scenes.

The titular Creature is a fish-human hybrid (known as Gill Man) living peacefully in an isolated lagoon in the Amazon jungle until a scientific expedition uncovers evidence of his existence (a claw caught in a fishing net). As the scientists search the lagoon, the Gill Man becomes enamored of one of the expedition members, Kay Lawrence (Julia Adams), fiancée of evolutionist Dr. David Reed (Richard Carlson). One of the most famous scenes in the movie is an underwater ballet: Kay swims on the surface as, unbeknownst to her, the Gill Man swoops and dives in the murky waters beneath. As the men hunt him – and he snaps back, killing them one by one – Gill Man’s affection for Kay only grows. In an echo of King Kong, he abducts her and attempts to carry her off to his watery lair, only to be almost destroyed (obviously not killed because: sequels) as her friends rescue her.

Gill Man’s fondness for human women also drives the two sequels that Universal released almost immediately to capitalize on their latest monster success. Jack Arnold also directed Revenge of The Creature (1955). Gill Man is captured and taken to an aquarium in Florida, where he’s put on display to the public and “trained” using electric shocks. He only puts up with this because he has a new crush – graduate student Helen Dobson (Lori Nelson). When he escapes the aquarium, he takes her with him, only to be almost-killed again.

John Sherwood is the director of The Creature Walks Among Us (1955). As the madness of science truly takes hold, the Gill Man is pursued by Dr. William Barton (Jeff Morrow) and his group of obsessed geneticists who want to study this new life form and use the knowledge to create a new race of beings. Barton brings his wife Marcia (Leigh Snowden) on the expedition as unwitting eye candy for Gill Man. This time, when the scientists capture the Creature, they mutilate him, destroying his gills, meaning he can no longer survive underwater. Gill Man’s fate after his final escape remains ambiguous.

Gill Man is considered the last of the Universal monsters and there have been many attempts to reboot his story as part of the Dark Universe IP reimagining. Certainly, the environmental warnings embedded within these stories about interfering with fragile ecologies and destroying rare species have only become more urgent over time. Guillermo del Toro was attached to a remake in the early 2000s. That never happened, but The Shape of Water (2017), del Toro’s dreamy rewriting of the Creature From The Black Lagoon mythos so that the Gill Man gets the girl, won the Academy Award for Best Picture.

These monster movies of the 1950s were the original blockbusters (a term first used in a 1951 Variety review of Quo Vadis), opening in US theatres coast-to-coast amidst a marketing storm of advertising and merchandise. They used the new medium of TV advertising to reach suburban and teenage audiences, and stunts involving giant dinosaurs and ants to reach the newspaper front pages. The idea was not to promote quality performances, but a big movie-going experience and lines around the block rewarded this strategy, twenty years before Jaws. Individual Creature Features may now have been largely forgotten, and only appeal to cultists prepared to forgive their creaky dialogue and now-clumsy SFX, but their collective memory is still cherished and still influences movie output (Jurassic World, Cloverfield, and The Meg to name but three).

Further Reading

- The Imagination of Disaster (essay) Susan Sontag in Against Interpretation (NY, Picador, 1966). Summary online.

- Debunking The Jaws Myth – Dade Hayes & Jonathan Bing (Variety article on 1950s blockbuster marketing)

- Move Over, Godzilla! Killer Bugs, Babes, and Beasts in 1950s Drive-in Cinema – Mark A. Vieira in Bright Lights Film Journal, 2014

- The Astounding B Monster – a comprehensive site devoted to all monsters B

- The Biology of B Movie Monsters – excellent assessment from a biologist of what really happens when creatures are scaled up and down in size

- The Fantastic Mystery of Milicent Patrick – Vincent di Fate on Tor.com

Stranded at the Drive-in: JDs, Sleaze & AIP

In 1956 James H. Nicholson & Samuel Z. Arkoff decided there was money to be made in supplying the bottom end of the cinema market with two-for-the-price-of-one movies. The B-picture was thought to be dead, the two-picture moviegoing experience usurped by the home comforts of television. However, Arkoff and Nicholson had a very specific audience in mind – one that enjoyed NOT sitting in the living room surrounded by close family members. Their company, American International Pictures catered very specifically to this new and growing market – teenagers.

In later years, Arkoff summed up the AIP formula as a mnemonic of his own name:

Action (which had to be fast-paced)

Revolution (new ideas for the new generation)

Killing (just enough violence to keep the kids happy)

Oratory (snappy dialogue)

Fantasy (– or Fornication, depending on who he was talking to)

Arkoff & Nicholson identified pop culture trends they felt would become popular with teenagers, came up with a catchy title and an ad image, and then let their in-house filmmakers Roger Corman and Herman Cohen loose on the lot with a miniscule budget. They cranked out 25-30 pictures a year this way, utilizing young, hungry, cheap talent – Jack Nicholson, Robert De Niro, Martin Scorsese, Francis Coppola, David Cronenberg and Dennis Hopper all got their start in an AIP movie.

“What elements made these AIP films shlock classics? They were simple, shot in a hurry, and so amateurish that one can see the shadow of a boom mike in the shot or catch the gleam of an air tank inside the monster suit of an underwater creature (as in The Attack of the Giant Leeches). Arkoff himself recalls that they rarely began with a completed script or even a coherent screen treatment, often money was committed to projects on the basis of a title that sounded commercial, such as Terror from the Year 5000 or The Brain Eaters, something that would make an eye-catching poster.”

— Danse Macabre by Stephen King p46

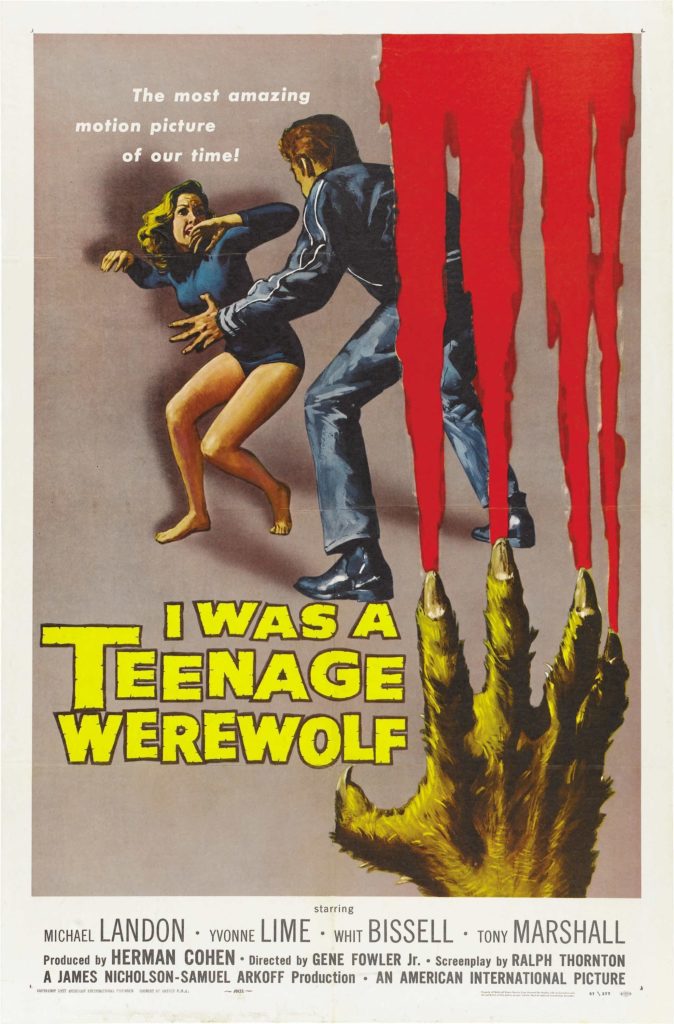

The cycle kicked off with a nod to The Wolf Man with I Was A Teenage Werewolf in 1957, and would go on to plunder other horror classics like Dracula and Frankenstein. There were original properties too, such as The Ghost In The Invisible Bikini (show me a teenager who doesn’t want to see THAT!!). By mixing and matching the stories that had come to be acknowledged as horror standards with current pop culture – and that included adding dance numbers – AIP shaped the teen horror market for decades to come.

Further Reading

- Monster At The Soda Shop on the Monster as a metaphor for juvenile delinquent

- A Teen Movie Machine – Patrick Goldstein, Los Angeles Times, May 10, 1998

Trick or Treat?

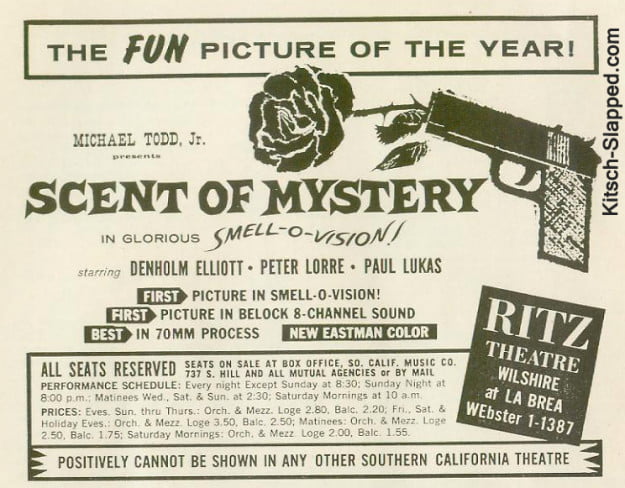

The 1950s saw a number of technical innovations in the cinema; CinemaScope, Cinerama, Stereophonic sound, 3-D and even Smell-O-Vision, all designed to lure the audience away from their TV sets. Whilst big-budget, full-technicolor Hollywood epics offered a real ‘big screen’ alternative, lower budget movies needed extra gimmicks to pull in the punters. One ex-music hall impresario, William Castle, understood what it took to get the audience actively involved in the horror experience, and, with his production company Castle Pictures, launched a series of gimmicks to draw the crowds.

- 6 Non 3-D Gimmicks From The Warped Mind of William Castle — Film School Rejects

The devices added to the fun of the horror movie experience, audiences screamed as much with laughter as anything else. This is the sort of shared experience delighted in by regular Saturday night viewers of The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) and is a concept deftly explored in the 1991 movie Popcorn (Tagline = Buy it in a box. Go home in a bag). Castle also toured the country exhibiting his movies, fully understanding that he could sell them by hyping screenings into events.

House on Haunted Hill (1959)

Another low budget shocker starring Vincent Price: an eccentric millionaire entices five unlucky souls into his haunted mansion with the promise of a cash prize if they can survive the night. It’s based in principle, if not in detail, on Shirley Jackson’s highly successful novel, The Haunting of Hill House (which Robert Wise turned into the classic chiller The Haunting four years later). Notorious penny-pincher Castle didn’t want to pay for the rights, hence the bowdlerized title.

Whilst the original novel concerns a cast of paranormal investigators seriously intrigued by the vibrations of a haunted property, this version is all about the quick shock and overnight survival of the fittest. Price presides over a veritable funhouse of shock and startle. But not all the surprises are on screen. Castle rigged a device called the Emergo, in selected cinemas, a glowing skeleton which, at a certain point in the film screeched out over the heads of the audience causing them to screech in delight.

The Tingler (1959)

Grossing over $2million off a $400,000 budget, The Tingler was another success for Castle, and is an object lesson in marketing hype. The story is, in the main, misogynistic melodrama, and the solitary insectoid monster that appears onscreen is just over a foot long. However, Castle’s showmanship and Vincent Price’s performance bring it to another level.

In the second of two movies Price made with Castle that year, he plays Dr. Warren Chapin, a gentleman-scientist fascinated by the concept of fear. While autopsying the bodies of executed prisoners he has observed that the vertebrae crack at the moment of execution, as though under some immense pressure which has nothing to do with the electrocution. He believes that there is some kind of fear-generated force which occupies a space at the base of the human spine and becomes obsessed with proving its physical existence. He dubs that force ‘the Tingler’.

Read more about THE TINGLER>>>>>>>

They Came From Outer Space

“That unidentified flying objects have been present since the dawn of man is an undeniable fact. They are not only described repeatedly in the Bible, but were also the subject of cave paintings made thousands of years before the Bible was written. And a strange procession of weird entities and flying creatures has been with us just as long. When you view the ancient references you are obliged to conclude that the presence of these objects and beings is a normal condition for this planet… They are not from outer space. There is no need for them to be. They have always been here.”

From The Mothman Prophecies by John A. Keel (1975)

“I saw what I saw. And no one can change my mind.”

Kenneth Arnold, 1947

On 24 June 1947, “businessman-pilot” Kenneth Arnold reported seeing nine strange, reflective objects as he flew his plane over Mt. Rainier one clear summer evening. He described them as “flying saucers”. The US government denied all knowledge or responsibility and showed little interest in Arnold’s report, thus generating a million and one conspiracy theories. The Unidentified Flying Object phenomenon was born.

With flying saucers firmly ensconced on newspaper front pages and radio talk shows, it wasn’t long before the movie world appropriated their pilots as a new cast of villains. Science Fiction had long made use of aliens as a threat, as reflected in the so-called ‘Golden Age’ of SciFi, running from the late 1930s to the 1950s. However, this golden sci-fi was restricted to the printed page – either pulp novel or comic book – as the movie-making technology simply wasn’t there to transfer the horrors from page to screen. However, technological advances, coupled with wild public interest, and the economic need to drag teens into the drive-ins, meant that by the mid-1950s, alien monsters were looming large on the silver screen. Technology, instead of being offscreen, in the form of lights, cameras etc, was firmly onscreen, in the form of shimmering spaceships and deadly ray guns.

There is a strong crossover – as there is in the 1980s – during the 1950s between horror and science fiction. Horror had painted itself into a corner by lampooning its great icons at the end of the 1940s. By uniting with science fiction, by wholeheartedly embracing the Atomic Age, there was a rebirth of credibility. As in the 1980s, the best horror embraced sci-fi in the 1950s as a way of critiquing society, of tellingly darkly allegorical tales where the threatening elements in society were given, not the faces of mad scientists or supernatural monsters, but Creatures from Outer Space.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956)

Invasion of the Bodysnatchers represents aliens as… well, human beings. Not just any human beings but next door neighbors, the kid down the street, the people of whom the fabric of your daily life consists. Based on the 1955 novel The Body Snatchers by Jack Finney, it posits a very simple, very terrifying theory: THEY have taken over. THEY look just like you. THEY have total control. THEY want to take you over now, and THEY are coming to get you. Often seen as a parable about communism in the McCarthy era, Invasion… works on a much deeper level than petty politics. The central discussion at the heart of the film revolves around the difference between a real human and a pod human “He looks just like Uncle Joe, and he acts just like Uncle Joe, but he ain’t Uncle Joe”.

The film tries to pin down what it is to be human, and the answer is a vague indefinable ‘something’ that only humans can recognize and pod aliens can’t replicate. The pod-humans are scary enough, bland, placid creatures who could blend into any whitebread community in small-town America. The pods are scarier still – oozing and throbbing in a greenhouse. At least Miles can deal with them using a gardening tool, which is more than can be said for the deep feeling of paranoia the film leaves you with. This is a giant of a movie in both the sci-fi and horror genres. The low budget is spent wisely – special effects are minimal, yet chilling and the performances are fine. It stands in movie history as one of the best horror/sci-fi films of the 1950s and has been much discussed, both as an early example of Don Siegel’s work (he went on to direct Dirty Harry and many other movies starring Clint Eastwood) and as a political allegory. Much has been made of the brainwashing theme and its relationship to both McCarthyism and the Red Peril.

Finney’s original story is so powerful it has been made into several different movie versions (of varying quality). It was remade in 1978 starring Donald Sutherland, as Body Snatchers(1993) (directed by Abel Ferrara) and as The Invasion in 2007 starring Daniel Craig and Nicole Kidman.

- Filmsite.org

- GadFly online – another critique, this one discussing the dehumanizing effect of the atomic bomb and how this is manifested in the movie

Plan 9 From Outer Space

At the other end of any scale, but made in the same year, Ed Wood’s Plan 9 From Outer Space deals with the same themes. Kind of. Aliens are hovering above Los Angeles, and are reanimating the ‘recently dead’ in order to form an army to bring down the governments of the world, who ignore the aliens’ presence and persist in their blind development of destructive weaponry. Dubbed The Worst Film Ever Made, Plan 9… demonstrates how easy it was to go wrong with the sci-fi/horror crossover – if you didn’t have the budget for the special effects, or the sense (as Don Siegel had) to stay away from them as much as possible.

Originally titled “Grave Robbers From Outer Space” Bela Lugosi was slated to star – but he died 5 months before filming was due to begin. Undeterred, Ed Wood left Lugosi’s name in the credits and got a local chiropractor to play the part (with a cloak over his face). Lugosi appears briefly at the beginning of the film, as Wood used some test footage he had shot of the actor a year or so previously. The rest of the film is a similar ragbag – long philosophical speeches from “aliens” (although suspiciously humanoid ones) about the essentially destructive nature of humans, dodgy flying saucers wobbling around on the end of strings, Vampira (who had been sacked from her TV presenting job for suspected communism) lurching around in a graveyard of cardboard tombstones, the “army” of three reanimated zombies, the interior of the alien spaceship which manages to put corners in a saucer… the list goes on.

The film’s production values are breathtakingly low, but Wood’s personal hedonism (he was said to type faster drunk than he did sober) and love for moviemaking shine through. This is D-movie stuff, but it has endured as a cult classic.

- The Unofficial Plan 9 Page

- badmovies.org – summary & review

- Graverobbers and Drag Queens – Gary Morris on Ed Wood April 1, 2000