Pediophobia and Agalmatophilia

CHILD’S PLAY (1988) relies on pediophobia, our irrational fear of dolls. Dolls are miniature, porcelain-perfect, simplified, immortal versions of human beings, so the terror they inspire is understandable. Any sensitive child (or adult) might panic at the sight of rows of glassy eyes staring down from a shelf in the toy cupboard, especially when toymakers take such pains to make their product ‘true-to-life’. Some dolls move, talk, cry, even defecate. They strive to be real, but rely on our fantasies to bring them alive. Creepy.

At the other end of the spectrum, doll fetishism or agalmatophilia, where the practitioners are attracted to inanimate objects such as dolls, mannequins and statues, dress as dolls or fantasize about being transformed into dolls, is an established subculture. Horror movies provide the perfect arena to explore this repulsion/attraction, whether the dolls in question are Good Guys or Golems.

Freud’s The Uncanny

In his 1925 essay The Uncanny , Freud says dolls are a trigger for the feeling of “unheimlich”, that skin-prickling sense of strangeness in the familiar. He cites “the impression made by waxwork figures, ingeniously constructed dolls and automata” as a sure source of fear, especially as it relates to our suspicion of “reflections in mirrors, of shadows”; anything that ‘doubles’ the human form is at once natural and unnatural, strange and familiar. Dolls are us, but not us. Their plastic limbs feel no pain, their silicon skin does not age, their hollow stomachs need no food.

Writers as diverse as Carlo Collodi (Pinocchio) and D.H. Lawrence (The Captain’s Doll) have employed dolls as sinister objects in their storytelling. Georges Méliès saw their potential in his 1908 film short La Poupée Vivante, and they have been exploited by film-makers ever since, most notably by Tod Browning (The Devil-Doll, 1936), Richard Attenborough and William Goldman (Magic, 1978) and the Puppet Master series (1989-2004).

Read more about creepy dolls at:

- LURID: Welcome to the Dollhouse @LitReactor

“Heeeeeeere’s Chucky!”

Child’s Play (1988) introduced horror audiences to Chucky, who, as well as drawing on the long tradition of malevolent dolls on page and screen, creates a bridge between the monster children of the 1970s and the serial killers of the 1990s. The self-aware irony pre-empted the tone of postmodern horror of the 1990s.

In human form, Charles Lee Ray (his name is a combination of notorious killers Charles Manson, James Earl Ray and Harvey Oswald) is just another weasel-faced small-time murderer who can’t catch a break. Transformed into Chucky, he’s a wisecracking invincible who never sleeps, whose bright, polymer-blue eyes make him seem innocent of any wrong-doing. Chucky can go far more places and do more things (mainly kill people) than Charles Lee Ray can dream of. These supernatural powers are a key element of his appeal throughout the franchise.

Visually, Chucky is terrifying, his toddler clothing, foreshortened limbs and freckles juxtaposed against a deadly snarl. Yet he is also fascinating, a very human non-human, no longer subject to the laws of the living, but bound by plastic restrictions. We want to run from Chucky, but part of us wonders what it would be like to be him.

Despite his limited size and plastic limbs, Chucky appears to be a more rounded character than either Jason Voorhees or Mike Myers. The films in the franchise demonstrate his complexity. Chucky runs the whole gamut from killer to clown without confusing his core branding. He’s funny, scary, angry and, in places, sympathetic. While his antics get increasingly comedic as the series wears on, Chucky is the same, a foul-mouthed, three feet high ex-con with cherubic cheeks. He has endeared himself to millions worldwide, and remains a popular Halloween costume when October rolls around.

The original writer, Mancini, stayed in creative control of the Child’s Play franchise, even directing the fifth instalment himself. As well as the movies, Chucky has generated mountains of merchandise, fan fiction, and a series of graphic novels and a TV show.

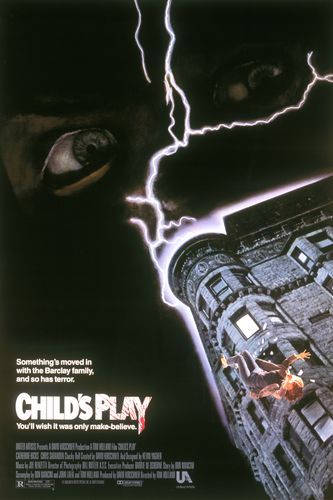

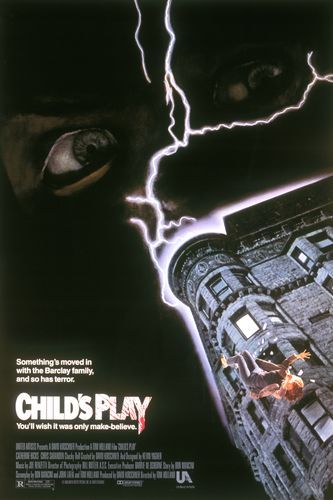

Child’s Play (1988)

Penned by then-UCLA student Don Mancini, CHILD’S PLAY follows a slasher paradigm with a unique twist. The serial-killer-inside-a-doll concept allows the film-makers and audience to play with genre conventions. There’s nothing plot-wise we haven’t seen before. The narrative focuses on the hunt for a brutal, inhuman murderer who must be stopped before he picks off all the main characters. However, choosing a blue-eyed, red-haired, dungareed doll as the killer was a bold new move in 1988. Chucky was iconic and original enough to invigorate the slasher paradigm. He provided a solid foundation for Universal’s multi-million dollar franchise.

Mancini’s screenplay wears its influences on its sleeve. In Act III, Chucky channels Jack Nicholson (in The Shining) and Arnold Schwarzenegger (Terminator) in short order. The narrative is structured for horror fans, who’ll relish each steadily-building suspense sequence and savage attack. Chucky stays in the background for the first half of the movie. He establishes a threat via half-glimpsed movement at the corner of the frame or the sound effect of his footsteps. Chucky’s swift, decisive actions, when they come, have the power to make the audience jump out of their seats. It’s all about shock/startle entertainment. The goal is visceral response rather than emotional terror. Two decades on, the animatronic puppet may have lost some of his power to scare an adult audience but he still invites us on a fun ride.

For a doll, Chucky’s got depth

We find Chucky sinister because he taps into our deep-rooted fear (as identified by Freud) of doubles and substitutes. For lonely, fatherless kids like Andy, Good Guy dolls provide substitute ‘friends to the end’. But this Chucky is a substitute substitute. Not only has his doll plasticity been exchanged for a human heart and soul, he’s also a back alley bait-and-switch. He’s a battered, knock off version of the real thing. Ideally, Andy would have a flesh and blood friend (perhaps even a father?), but he’s denied that opportunity. So his mother’s search for an artificial substitute leads into dangerous — but familiar to fans of science fiction such as BLADE RUNNER and A.I.:ARTIFICAL INTELLIGENCE — territory indeed. One poster image (below) deliberately invokes FRANKENSTEIN.

Voodoo Child’s Play

In the years before cultural appropriation was viewed as problematic, voodoo was a go-to for horror movies, especially if they involved dolls. Mancini embraces the concept of soul transfer used in many other movies (from Devil Dolls to The Skeleton Key). The rite is straightforward yet misfires. Charles Lee Ray chants a spell he hopes will save him from the electric chair. He only manages to generate a high voltage shock and subject himself to an even worse fate than death. Yes, he’s indestructible as a doll, but on many levels this new manifestation sucks. Charles finds himself returning (regressing?) to his original, fragile form.

His fatal flaw, a human, beating heart, encased in a plastic chest, is a grisly touch, straight out of Edgar Allen Poe, and ties Child’s Play to the body horror of this era. Charles Lee Ray undergoes a similar transformation to Seth Brundle in The Fly, meshing his human form with an Other. But while Seth is a victim of science gone wrong and can find no way back, Charles believes he can wriggle out of the curse. Where medicine fails, magic will prevail.

Characterization

While Brad Dourif’s sinister, snickering voice work brings Chucky to vivid life, Alex Vincent’s portrayal of Andy is probably the most poignant and unnerving aspect of the movie. Rarely has a child actor (especially one in a horror film) played it so real. The veracity of his performance terrified so many under-10s who accidentally encountered this movie on cable TV back in the day. Andy is close cousin to the kid characters favoured by Spielberg. Abandoned by his father and neglected by his single Mom, all this child of the 80s wants is a friend. But instead of buddying up with an amicable alien, he latches on to a demonic doll who turns out to be hell-bent on his destruction — be very careful what you wish for.

While Chucky is clearly an adult – his lewd obscenities a specific aspect of his grotesqueness – Andy deals with him as if he were another child. There are hints during the first 20 minutes of the movie that Chucky might represent one of Andy’s repressed, murderous personalities but, as Act II progresses, Chucky is the cuckoo child, invading the nest. Chucky doesn’t want to co-exist with Andy. He wants to usurp him, even if it means the hard-nosed hitman in the driver’s seat has to live with being six years old again.

Once he realizes what’s really going on, Andy responds to the threat in a resourceful, but still childlike way. He hides in the closet (shades of Jamie Lee Curtis in HALLOWEEN), and rummages in his toy box for weapons he can use in his defence. He tells his Mom he’s in danger, over and over again, but she insists the monster isn’t real. This strikes a nerve in anyone who has ever experienced adult inattention. It’s more chilling because Andy barely survives. His life is irrevocably damaged by Chucky’s presence. Further consequences of his brush with the demon doll are played out in later instalments.

Child’s Play Sequels

There have been a grand total of seven Chucky movies (1988-2017) with a TV series airing in 2021. Here’s a handy animated guide:

Useful Links

- Tom Holland’s commentary – downloadable thanks to Icons of Fright.com

- Love in the Age of Silicone – an exploration of agalmatophilia by Meghan Laslocky