Rosemary’s Baby (1968) expresses some of the anxieties about evil children explored in The Bad Seed (1956) and Village of The Damned (1960) (an adaptation of John Wyndham’s The Midwich Cuckoos). It also tapped into the ongoing debate about a woman’s right to choose – if only Rosemary could have marched into Planned Parenthood for some objective medical advice, instead of falling under the control of religious maniacs! This wildly influential movie paved the way for the evil children movies of the 1970s (from It’s Alive to Alien) and is referenced heavily by current horror filmmakers (see: Get Out and Hereditary).

Continue reading “Rosemary’s Baby (1968)”Tag: USA

Room 237 (2012)

Room 237 takes us on a fascinating dive through the minds of individuals who have scanned back and forth through The Shining so many times that they can make it mean anything they choose.

No other movie divides opinion quite like The Shining. Hailed alternately as a work of genius and a confused mess, people either love it or hate it. Haters include the author of the source material, Stephen King, who called it “a film by a man who thinks too much and feels too little”. It left critics scratching their heads – Roger Ebert confessed himself disturbed by the “elusive open-endedness” while Pauline Kael declared “Kubrick mystifies us deliberately”. Yet for every moviegoer who rejects The Shining as cold and impenetrable, there’s one who embraces it as a masterpiece. There are even some people who believe its ambiguity holds the key to the great mysteries of modern civilization.

Room 237 takes us on a fascinating dive through the minds of this last group, the individuals who have scanned back and forth through The Shining so many times that they can make it mean anything they choose. Across the board, these conspiracists agree that there was no way an auteur like Kubrick would be satisfied with making “just” a horror film, especially if it were an adaptation of King’s pop fiction. Ergo, it must be an elaborately coded message, a deeply symbolic ride through Kubrick’s secret anxieties – all the stuff he felt unable to say out loud. They insist there must be more to The Shining than three people trapped by snow in a haunted hotel. They believe that with Kubrick there are supposedly no accidents, no continuity errors, no on-set flubs. Says Room 237 producer Tim Kirk, “Just because he was so known to be so meticulous and such a perfectionist with multiple takes and so forth, there’s this feeling that if there’s anything in the frame he put it there. There’s a reason, and that reason can be determined.” Director Rod Ascher agrees that Kubrick is considered infallible in many quarters. “If you don’t understand something it’s not his mistake, it’s your problem.”

Without doubt, The Shining doesn’t quite make sense. Ascher describes it as

“a puzzle that’s missing a few pieces. Even at the simplest level of story there’s huge gaps in what we know about what goes on in it. The central event of the film – what happens to Danny in Room 237 – is never explained, let alone shown. That black and white photo at the end is presented as if it was the answer to some kind of puzzle that we had all along, but if anything, it’s an entirely new question about what’s happening in the film. I think people are attracted to watch it and re-watch it, to try to solve those sorts of puzzles, and they find all these new ones.”

And, in the three decades since its release, the movie has compelled many, many people to watch and re-watch it, patiently spooling through VHS copies in the years before DVD, coming up with their own explanation for what might really be going on. The theories represented in Room 237 are by turns Byzantine, baffling, and completely believable. That’s the thing about listening to a conspiracist expand on their hypothesis – after a while, it all starts to fall into place and you wonder why you didn’t see any of this before. The conspiracists assembled by Ascher and Kirk are an eloquent, dedicated bunch who’ve spent years assembling and road-testing their hypotheses about the film. Although there are many, many more theories out there, Room 237 goes with the ideas of veteran foreign and domestic correspondent Bill Blakemore, professor of history Geoffrey Cocks, playwright Julie Kearns, musician and culture-jammer John Fell Ryan, and author, filmmaker and hermetic scholar Jay Weidner. They’re all very plausible — to a degree – although some of the more outlandish claims about seeing Kubrick’s face in the clouds or genocide in a tin of baking powder may be detrimental to the overall cause.

Ascher makes a deliberate choice not to show his Shinologists’ faces on screen. Instead, he weaves their interviews over a subjective stream of images from The Shining and Kubrick’s other works, using sequences from Barry Lyndon, Eyes Wide Shut, A Clockwork Orange, 2001: A Space Odyssey and Lolita to habituate the audience to the director’s mindset. This serves as a constant reminder that with Kubrick, every filmic element in every shot has specific meaning, from mise en scène to music to framing to the overlap within a dissolve. Given the absolute precision with which Kubrick pieced together the semantic layers in – for instance – the décor of the hotel scenes in 2001, it would seem foolish to assume he wouldn’t approach the tapestries and carpets of the Overlook with the same meticulous attention to detail and depth of meaning. Or would it?

For the skeptics among you, the theories discussed in Room 237 won’t hold water. Leon Vitali, assistant to Kubrick at the time of The Shining, dismisses the documentary as “gibberish”. Unfortunately, Kubrick, the only man who could attest to what was going on in his head during filming, is long dead. If he did have these elaborate intentions about the deeper meaning of the movie, he didn’t tell anyone he was working with at the time. There are many, many stories told by the crew who spent a year shooting The Shining on the backlot of Elstree Studios in the UK. Most of them focus on the technical challenges involved in navigating cameras around the rambling, multi-stage set, or the contrast between the easy camaraderie Kubrick had going with Jack Nicholson and the callousness with which he treated Shelley Duvall. There’s plenty of material on the record. The then-17 year-old Vivian Kubrick shot a ‘Making Of…’ documentary that included some very candid moments of the actors working with her father.

Part of the Elstree Project, Staircases To Nowhere collects other slices of oral history about the unique experience that was principal photography on The Shining. These transparent, first hand accounts contain no mention of the moon landings or the Holocaust, or indeed any agenda Kubrick might have had other than making each frame of film as disturbing as possible.

But that’s the joy of Room 237. It’s an absorbing movie-about-a-movie that doesn’t, for once, labor the behind-the-scenes trauma that’s often required to make art, but instead focuses on the pleasures of the text. It examines the purity of the relationship between viewer and screen, especially when the viewer is determined to weave their personal obsessions into their construction of meaning. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter what Kubrick was thinking when he changed the color of Jack’s typewriter – it’s about what you believe it means. Like The Shining, you’re either going to love or hate Room 237. Nonetheless, it will get you pondering the cognitive processes involved in watching a movie. It may even give you some insights into what might be going on in the head of the person sitting next to you in the theater. Saturday night at the multiplex will never be the same again.

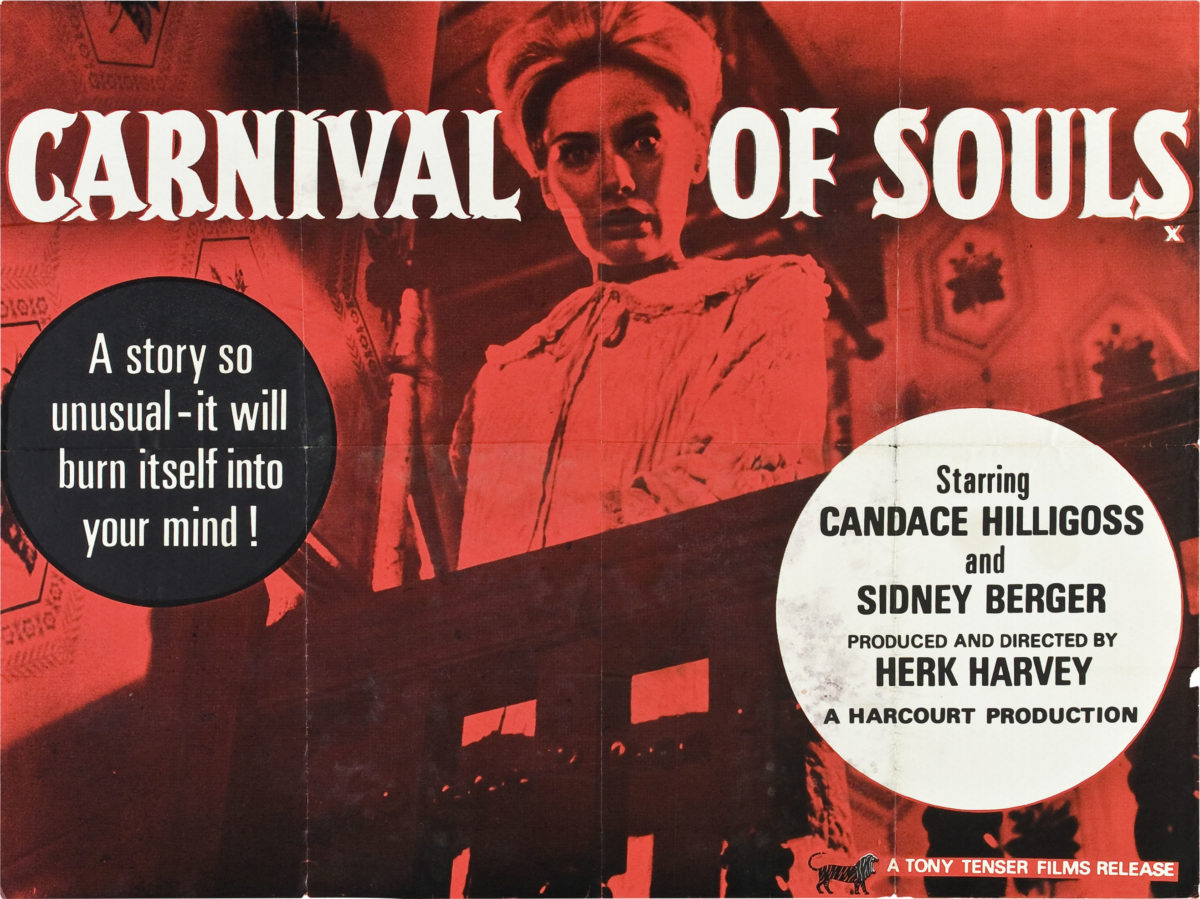

Carnival of Souls (1962)

Carnival of Souls is a low-budget gem, a cult horror film that retains its power to haunt the viewer almost sixty years after it was first released.

Continue reading “Carnival of Souls (1962)”Werewolf of London (1935)

![]()

“The werewolf is neither man nor wolf but a satanic creature with the worst qualities of both.”

This movie represents the first attempt by Hollywood to bring werewolf mythology to the big screen. Mannered and stylized — one of the first horror films produced entirely under the restrictions of the Hays Code — it contains some intriguing ideas about the nature of hybridization, and along with a very simian werewolf. It’s most significant for the way in which it connects the Jekyll and Hyde mythology to the idea of transforming into an animal, rather than a corrupted form of human being.