Freaks is a rarity, a horror film that horrifies rather than frightens. It was critically destroyed on its release in 1932, blamed for the downhill career trajectories thereafter of the key players, and banned in many countries for more than thirty years. Yet in 1994 it was selected for the National Film Registry’s archives, and now enjoys both cult and canon status. It’s a film both of its time (starring a strata of freakshow performers who no longer exist on a public stage) and ahead of its time, extending the definition of ‘sympathetic characters’ way beyond a 1932 audience’s limits.

The Director

Tod Browning was born to make Freaks. He ran away to join the carnival at the age of sixteen, in 1896 when the sideshow tradition was in full swing: fuelled by PT Barnum in the mid years of the nineteenth century, Americans flocked to the carny, eager to see Fat Ladies, Fiji Mermaids and Frog Boys. Before cinema, before television, the sideshow was a cabinet of curiosities where actual freaks of nature and those who modified themselves to be that way (so-called “gaffed” freaks) provided pure entertainment.

Browning began his carnival career as a barker, drumming up trade for a Wild Man of Borneo. He supposedly also did stints as an escapologist, a clown, a stunt horseback rider, a contortionist, illusionist and tap-dancer. At the same time, cinema was also making its name as a sideshow attraction: alongside the Living Skeletons and Bearded Women, kinetoscopes were drawing a crowd. As the first nickelodeons opened across America in 1900, it was becoming clear that the sideshow had a challenger when it came to the exhibition of signs and wonders.

Browning got his first break in cinema in 1913, appearing (as an undertaker, no less) in a DW Griffith comedy, Scenting A Terrible Crime. He moved with Griffith to Hollywood the following year and branched out into directing. However, his career was dogged by his alcoholism. A car accident in 1915 took him to death’s door, and although he directed several successful pictures on his recovery, he was seen as a bad risk by the studios. He was virtually blacklisted in 1923-4. His comeback assignment, The Unholy Three (1925), was a crime melodrama involving three sideshow oddities and a jewel heist and is remarkable for its sympathetic portrayal of the outsider antiheroes. This was another collaboration between Lon Chaney, Sr (who played Echo the ventriloquist) and Browning. It also marked the first screen appearance of the midget, Harry Earles, as Tweedledee, the grown man who poses as a baby to chilling effect. It was a huge hit for MGM, and, subsequently, the studio gave Browning creative licence to mine his macabre past.

Browning enjoyed collaborating with Chaney Sr. and went on to direct him in The Road To Mandalay (1927) (Chaney plays a one-eyed gangster) and The Unknown (1927) (Chaney as an armless knife thrower falls impossibly in love with circus girl Joan Crawford). During this time he also directed London After Midnight (1927) (an ill-fated vampire movie last seen perishing in an MGM fire in 1965). Despite their dark matter, the pictures were extremely successful — at one point Browning boasted that MGM paid him a salary of $150,000, twice that of the US President, although this is undoubtedly a showman’s exaggeration. His uncanny vision made him a shoo-in to helm Dracula when Universal won the rights to the successful stage version.

Unfortunately, Browning did not find the transition to talkies easy (he was used to continuously directing actors as they worked) and his long-time collaborator, Chaney, died of throat cancer in June 1930 (Chaney was meant to take the role of the Count). By the time principal photography began on the pic, Browning was drinking heavily once more, and legend has it that much of the direction was done by the cinematographer, Karl Freund. The movie itself is something of a [monster] mishmash; partly because of Browning’s lack of control on set, partly because of the cuts demanded by Universal. Nonetheless, its massive box office success meant that Browning returned to MGM on something of a high note, and was able to devote himself to his next chosen project, Freaks.

The Source

The Unholy Three was based on a 1917 novel by Clarence “Tod” Robbins. Harry Earles, aware that good roles for midgets didn’t grow on trees, brought Browning’s attention to a short story, Spurs, by the same author. Like The Unknown, it centred round a love triangle between a circus freak, a “normal” circus girl and her lover.

The original story is a lot more mean spirited than the eventual screenplay; a greedy bareback rider named Jeanne Marie agrees to marry a wealthy midget, thinking he’ll die young, despite the fact that she is really in love with another regular sized performer. At the drunken wedding feast, Jeanne jiggles the midget on her shoulders like a child, boasting that she can carry him from one end of France to the other. The midget lays on a literal punishment, straight out of the Brothers Grimm, riding her up and down French back roads, forcing her on with a malicious set of spurs, until Jeanne’s circus lover no longer recognises the aged and exhausted wretch.

Spurs appeared in Munsey’s Magazine in 1923, and MGM paid $8000 for the rights, possibly intending it as a Browning vehicle from the get-go. MGM wanted a horror property to rival those being cranked out at Universal, and it seemed, in this backstage circus tale, that the ‘glamour studio’ might have hit the mark. Reportedly, Browning promised Irving Thalberg the ultimate horror picture. Thalberg was certainly horrified by what he got.

The Movie

SPOILERS AHEAD!

Freaks begins with a classic enigma – What’s In The Box? A crowd gathers around an animal pen, eager for the latest sideshow marvel, and hears the caution in the tale —

“We told you we had living, breathing monstrosities. You laughed at them, yet but for the accident of birth, you might be even as they are! They did not ask to be brought into the world, but into the world they came.”

The monstrosity remains hidden from view; all we know is that “she was once a beautiful woman”, now she elicits shrieks and gasps of horror. What she is now is best left to the mind’s eye, and audiences have an hour to ponder the question before finally being allowed to peer inside the pen, an hour in which all manner of human oddities and deformities, often defying imagination, are paraded across the screen.

Our freak’s story begins when she was “once known as the Peacock of the Air”, a fêted trapeze artist, and we segue into the backstage world of the circus. Notably, the circus acts are never represented onscreen, freak or non-freak, the action remains resolutely out of the ring. As befits an MGM picture, sequinned costumes abound, although Browning mixes and matches them with dirty t-shirts and overalls.

We’re plunged straight into sexual intrigue, as Cleopatra (Olga Baclanova) the trapezist, flirts with Hans the midget (Harry Earles), much to the chagrin of Frieda (Daisy Earles), his equally diminutive fianceé. The Hays Code was just coming into force, and it is difficult to know what might have stunned audiences of the day more — the intimation that midget/normal size sexual activity was on the cards (with all the connotations of paedophilia, given the midget’s child-like appearance), or the sheer licentiousness with which Cleopatra slides her cloak to the ground for an adoring Hans to pick up.

Without pausing for breath, Browning introduces a whole gallery of freaks, harking back to his old carnival tendencies for sideshow display. We meet Madame Tetrallini and her clan of Pinheads (actually microcephalics), out picnicking with the dwarf Little Angelo, and Johnny (played by Johnny Eck, the Astounding Half Boy). A growly peasant tries to get them evicted by the landowner (“There must be a law in France to smother such things at birth”), but when Mme Tetrallini pleads for her “children” to be allowed to stay, (channelling Snow White by gathering the little people in her skirts), the gruff lord of the manor relents. In the first half of the movie at least, the Freaks are usually represented as childlike, harmless, more frightened of strangers than strangers are of them. Back at the circus, non-freak performers indulge in banter with Joseph/Josephine, the hermaphrodite, and we meet Roscoe the stuttering clown.

It’s a good ten minutes into the 62 minute running time before the sympathetic non-freak characters are introduced; Venus the seal trainer (Leila Hyams — reportedly, Myrna Loy pleaded with Thalberg NOT to do the role) and Phroso the clown (Wallace Ford). Venus has been co-habiting with the Strong Man, Hercules (Henry Victor); we first meet her gathering up her possessions from his caravan and slinging insults as she departs. Phroso is immediately on the alert, and immediately offers his sympathies, but Venus is on her high horse and turns on him: “Women are funny, ain’t they? They’re all tramps, ain’t they?” This is a familiar enough scenario from melodramas of the day to allow the audience to relax a little. Regular people, having regular arguments. But, just as Venus is beginning to warm to Phroso (“You’re a pretty good kid”), he reminds her never to judge by appearances (“You’re damn right I am. You should have caught me before my operation.”).

Respite over, we meet Daisy and Violet, played by the Hilton sisters, aristocrats of the freakshow world. Siamese twins (they were fused at the pelvis, shared blood circulation but no major organs) born out of wedlock in 1908 to an unknown bartender, they were allegedly sold straight to a carnival owner and were sideshow performers from the age of three. Browning presents them as flirtatious and coy, managing to conduct separate courtships with two very different individuals. The freaks as a group have normal relationships in this world – the Bearded Lady gives birth, and her husband, the Living Skeleton, hands round cigars like any other proud papa. The only jarring note in the middle of all this harmony is Cleopatra, as she entices the newly-single Strong Man into her caravan with a line worthy of Mae West: “Feel like eating something?” “Always,” replies Hercules.

Horror seems a very long way away as the narrative meanders through a series of vignettes showing the domesticity of the freaks; they eat, drink, and peg out laundry, unremarkable everyday acts made remarkable only by the lack of arms, or legs, or even both. Browning frames freakish bit players as absolutely normal, such as Frances O’Conner, an armless blonde, sipping tea with her feet. The audience is bombarded with many so-called monstrosities, none of which present any threat whatsoever. The only menace stems from Cleopatra, plotting with Hercules and duping poor Hans into buying her furs and jewels. Whilst the freaks (and Venus and Phroso) are gentle and courteous towards one another, Hercules and Cleopatra mock Hans, calling him “the little polliwog” (an antiquated English term for tadpole), with the Strong Man threatening to “squish him like a bug.” Kind, loving Frieda can only watch as her beloved becomes more and more besotted with the trapeze artist, and eventually asks for Cleopatra’s hand in marriage.

Browning introduces the second half of the movie with a title card: The Wedding Feast. This marks an absolute change in pace, tone and mood. Gone are the child-like behaviour and tender domesticity previously displayed by the freaks as they carouse after the wedding. Koo Koo the Bird Girl shimmies her hips on the table; it’s crude burlesque for an adult audience, and the freaks roar drunken approval. The only people not to have noted the change in temperature are Hercules and Cleopatra, who kiss passionately, and then mock the simmering resentment of the new groom. Cleopatra jeers at Hans, calling him “my little green-eyed monster.” However, the freaks are prepared to overlook even this indiscretion, and toast Cleopatra with the ultimate honour —“We accept her as one of us. ”

Little Angelo passes a Loving Cup around the table, but when it comes to the bride’s turn to quaff, Cleopatra, horrified at the prospect of shared saliva, screams “You dirty slimy freaks!” and tosses the cup back in Angelo’s face. Equally horrified, the freaks, including a tearful Frieda, can only watch as Cleopatra hauls her new husband onto her shoulders and proceeds to galumph up and down cackling “Must Mama take you horsy back ride?” This is the ultimate humiliation for Hans, especially as it’s the closest he will get to wedding night sex.

From here on in the gloves are off. No longer innocent and infantile, the freaks peer through windows and from under caravans, keeping a constant watch on Hans, whom Cleopatra is, rather obviously, attempting to poison. We never see the freaks plotting, but from the moment Hans spits out his “medicine” it appears that a cohesive plan has come into play. Part of the terror of the final is the sense that events are heading towards an inexorable conclusion; the freaks will not be denied satisfaction once they choose to reach for it. Who came up with the plan? Who is the freaks’ leader? It doesn’t matter — they act as a unit, preying on those, like us, who might have been fooled by their childlike exterior. “Offend one and you offend them all.” Cleopatra’s doom is sealed.

As the circus ups sticks and prepares to trundle off to its next destination a storm gathers. So do the freaks, scuttling unseen under the caravan wheels to an assembly point, dividing into teams, those who will wait in grim-faced vigil in one caravan, and those who will stand guard over Hans. Even sweet-faced Frieda is part of the plot, warning Phroso that Hercules plans to attack Venus. When Cleopatra comes to give her husband his “medicine” she is unnerved to discover a panpipe-playing Little Angelo, plus friends, watching over the sickbed. Hans confronts Cleopatra, demanding that she “give me that little black bottle”. Angelo never misses a note of his spooky pipe lament. Faced with the unforgiving freaks, Cleopatra cannot lie, cheat or charm her way out of her lies. For the first time, she is helpless at the hands of her diminutive husband. And his switchblade brandishing friends, who, if it weren’t for their short stature, could be straight out of a Warners gangster pic.

Meanwhile, Phroso intervenes to save Venus from attack by Hercules. The plucky clown doesn’t fare so well against the Strong Man until he is aided by a knife throwing dwarf. The freaks seem to be everywhere at once – presumably they haven’t left Olga and Hans alone in their caravan? – and advance relentlessly through the rain. Even the jolly pinhead Schlitze, previously represented as giggling in delight at the slightest joke, threatens violence with a blade. The armless, legless Prince Randian slithers through the mud towards the wounded Strong Man and it’s clear Hercules’s number is up.

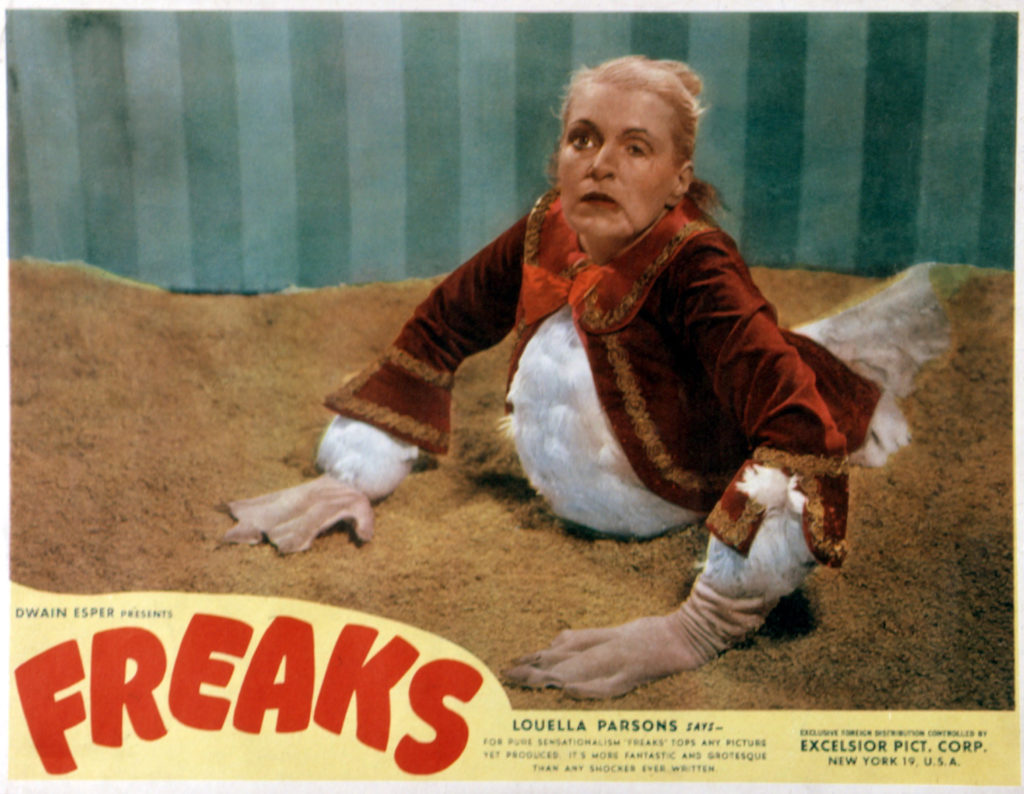

So too is Cleopatra’s. She runs, screaming “Help Me!” into the rain, pursued by freaks, agile and inexorable, including a fierce-looking Hans. She is never seen in non-freak form again. She is the thing in a box, now revealed to be another form of ‘Bird Girl’, a squawking, legless imbecile, her beautiful face and form ruined. This is both revelation and relief, like all good sideshow freaks she is not as terrifying as she might be, she doesn’t quite live up to the hype of the barker and our imaginations.

Instead of leaving us with some Jacobean morality tale, Browning adds a coda, designed to humanise the monsters once more. Phroso and Venus take Frieda to see Hans, who has fled the circus and become a recluse. The full-sized lovers leave the midgets alone, for Hans to express regret and for Frieda to absolve him from all blame. “You tried to stop them, it wasn’t your fault,” coos Frieda, as she takes her former fiancé in her arms. The final words of the movie are “I love you”, repeated twice. Frieda is back where she believes she belongs. Perhaps Cleopatra’s hideous fate was her doing all along, after all, hell hath no fury like a woman scorned, even when that woman has the face and dimensions of a cherub.

Afterburn

The studio was very unhappy with the director’s cut and tried three alternate endings on preview audiences. When it was finally premiered, in San Diego in January 1932, audiences were horrified, rather than frightened. The backlash against the movie came from the public and critics alike, and it was quietly withdrawn from theatrical release. Browning made a couple more movies (including the excellent Devil Doll in 1935), but between Freaks’ reputation and his alcoholism, he was finished. Several of the freaks, in particular Olga the Bearded Lady, regretted their involvement in the movie, which they came to see as exploitative.

It was banned outright in Britain and other countries and languished in vaults for more than thirty years until it was premiered anew at the 1962 Cannes Film Festival to great acclaim. A new generation had claimed the word “freak” as their own, and the film found new life on the counter-culture arthouse circuit, where it has remained a staple for years. The film has been read in varying ways — as a commentary on the studio system that treated all its talent like sideshow performers, as trashy exploitation, as a poignant fairy tale, as a grim morality play — but it is truly one of those few films that once seen, is never forgotten.

Its influence has been immeasurable on a diverse range of texts; HBO’s Carnivale and U2’s All I Want Is You music video flew the Freaks flag while James Herbert’s novel Others and X-Files episode Humbug (Season 2) reflect a pre-millennial fascination with the sideshow themes. There are several purported remakes out there, from the bizarre Freakmaker (1974) starring Donald Pleasance and Tom Baker to straight-to-DVD schlockmeisters Asylum Studio’s Freakshow (2007) which also stars “real” freaks. Ryan Murphy couldn’t have made American Horror Story: Freak Show without it.

The strength of its influence comes not from its art (the moviemaking itself pushes no boundaries) but its subject matter; the fascination we as human beings have with those who are different. Congenital deformity, then as now, fires public interest. A quick scan of 2007 news stories shows an international obsession with Lakshmi, the Indian girl born with four arms and four legs. But true difference — deformity, abnormality — is rarely put on public show these days. It is seen as insulting and derogatory to offer up the disabled for entertainment purposes, although audiences are happy to accept all manner of the grotesque, so long as it’s faked by SFX.

Freaks puts authentic difference and disability right up there on screen, and many people still find it a difficult viewing experience. The movie invites us to see the carny sideshow world as normal, where people hang laundry out to dry and roll cigarettes and get engaged and have babies just like anywhere else. Director Tod Browning takes us right through the looking glass and out the other side, makes the ‘normals’ into freakish monsters, tweaks our perceptions and makes us look at our own world with new eyes. Freaks‘ reputation is justly deserved.

©Karina Wilson 2000-2017