In Se7en, David Fincher (best known at the time for directing Madonna videos and the poorly-received Alien3) presents us with a narrative that, at first glance, seems straight out of the “young cop-old cop” buddy movie textbook. Somerset (Morgan Freeman), a quintessential, on the literal brink of retirement, middle-aged cop is paired with a brash rookie, David Mills (Brad Pitt). In a reversal of the usual “salt-and-pepper” pairing, the white Mills is the young, hot-headed partner while black Somerset provides the gravitas.

It’s easy to predict the main beats of the plot from this familiar genre premise. Initially the two cops clash, but are brought together by a common goal. Over time, they grudgingly gain admiration for each others’ working methods. Meanwhile, a strange bond, framed by parallel circumstances, grows between the lead cop and the killer, allowing them unique insights into one another’s modus operandi. The narrative climaxes in a showdown with an as yet unseen antagonist, probably involving someone near and dear to one of the cops to give that added emotional edge. The two cops need to depend on each other for survival and put aside their differences in order to triumph over evil. Se7en acknowledges all these expectations while twisting convention in ways you don’t see coming.

Like Silence of the Lambs, Se7en blends a basic procedural with horror paradigms. The result is so much more than a story about cops chasing a criminal. Firstly, Doe is no ordinary killer. A true psychopath, he believes his cruel intentions elevate him above the rest of humanity, rather than making him a monster. He doesn’t suffer from loss of control – quite the opposite. Everything he does is considered, deliberate, part of his grand scheme. He doesn’t attack his victims on impulse, or in anger, or vengeance, or for sexual satisfaction (as far as we’re told). He’s motivated by a higher purpose and, like Lecter, wields death as a way of expressing the sublime. He stages his crime scenes as elaborately constructed tableaux, as drenched in symbolism as a Renaissance painting. He mythologizes how his victims lived by matching them to a specific, and often tortuous, cause of death.

The Screenplay

Andrew Kevin Walker’s original script wears its literary influences on its sleeve. Most obviously, Doe’s grand plan is based on the ‘Purgatorio’ section of Dante’s Divine Comedy, written between 1308–21. As Virgil led Dante, so Somerset leads Mills on a pilgrimage through Fincher’s take on the Mount of Purgatory. It’s 1995, so seven levels of suffering exist in a rain-soaked, sepia-hued, decaying city. Walker also draws on the medieval morality play, The Summoning of Everyman, which tells of God’s anger at the sinful lives of mortals. As befits this literary framework, Somerset searches for clues in the library, quotes Hemingway, refers to Milton, the Bible, and Shakespeare (the Greed murder is a neat riff on The Merchant of Venice), and wonders out loud if the killer he seeks is “Satan himself”.

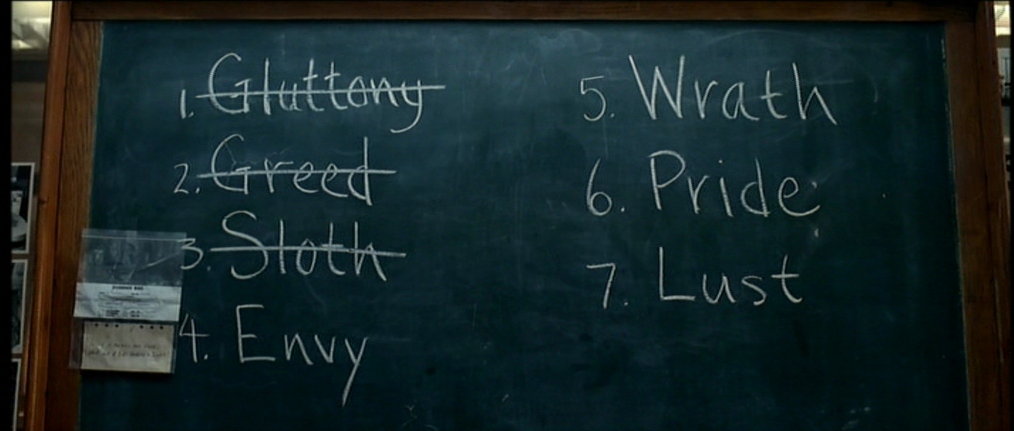

Structurally, Se7en entwines around the number 7; 7 days before Somerset retires, 7 victims for our killer to provide, 7 deadly sins for Mills to identify, key events on the hour of 7. There’s a mathematical beauty to the storytelling. Yet, at the top of the third act, Walker shatters the carefully built fictional construct, handing his killer over after just FIVE murders. That killer is Jonathan Doe; small, subdued, seemingly incapable of atrocity, but speaking for the dark heart in all of us with a character-defining monologue in the back of the police car:

We see a deadly sin on every street corner, in every home, and we tolerate it. We tolerate it because it’s common, it’s trivial. We tolerate it morning, noon, and night. Well, not anymore. I’m setting the example. And what I’ve done is going to be puzzled over, and studied, and followed… forever.

Pure/Evil Genius

With Doe, Walker takes Hannibal Lecter to the next level. In The Silence of the Lambs (although not so much in later instalments) Dr. Lecter demonstrates his evil genius through brilliant improvisation, bending circumstances (especially the foolish choices of other people) to his will. Anthony Hopkins gives Lecter a burly physical presence too – he’s strong enough to kill with his bare hands.

By contrast, Doe is a diminutive paperpusher who leaves much of the physical work of murder up to others. He’s much more concerned with the message he’s sending. Each of his crimes is a carefully crafted homily, highlighting the reality of contemporary sin. He’s too modest and assuming to preach these sermons himself. Instead, he relies on a violence-obsessed media to broadcast his deeds across the city. He also relies on Somerset to interpret the multi-layered symbolism of each crime scene, in the deliberate clues and textual references hidden just beneath the surface.

Doe’s true devilry lies in these symbolic details. For a full calendar year in advance, he immobilizes and tortures Sloth. He amputates Sloth’s hand so he can write a secret message on the wall of the Greed scene. He gives Pride the option to kill herself rather than live with a mutilated face. He shaves the skin off his own hands to remove his fingerprints. He even volunteers himself as one of his own victims, humbly claiming the Envy slot. One of Se7en‘s most horrific cruelties is the way Doe structures the circumstances of each killing so his victims have a certain amount of free will. To a certain extent, they all collude in their own deaths. If they vigorously, painfully, repented of their sin, they might save themselves. None of them can do it.

And it’s not as if they haven’t been warned. Evagrius Ponticus and Saint John Cassian first categorized ‘Evil Thoughts’ in the 300s. Pope Gregory I revised the list and incorporated the concept of ‘Seven Deadly Sins’ into Catholic doctrine in 590 CE. The writing has been on the wall for hundreds of years. In the godless end-of-times (1995), only a baroque serial killer could get people to read – and heed – it. Doe isn’t inventing a new or amoral universe. He’s simply reminding us to obey the rules of the one we already have.

Doe’s moral purity, more than anything else, is what makes Se7en so terrifying. He occupies the moral high ground right until the end as technically, he doesn’t commit the murders himself – except possibly Gluttony, but since when did a kick in the stomach kill a man? The only blood on his hands comes from his removal of his fingerprints. He merely sets the stage, relying on the forces of biology (Gluttony, Sloth, Greed) and the character weaknesses of other people (Lust, Pride, Wrath) to finish the job.

Doe is a gifted observer of human nature who identifies the sin inside people and skewers them with it. A good detective does the same thing and Somerset acknowledges the parallels as he follows – and appreciates – his suspect’s trail. Cop and killer share the same purpose in life – to clean up the city. They also share a desire to make the world a better place. Ultimately, it’s up to the audience to decide who succeeds and who fails.

Title Sequence

“David Fincher, the director, wanted the titles to say to the people expecting to see Brad Pitt and Morgan Freeman in movies like ‘Legends of the Fall’ that they were in the wrong theater… He mentioned that he wanted something that could have sent them screaming from the theater, just the titles alone. I kind of think we pushed the envelope.”

Kyle Cooper, quoted in the New York Times, March 24, 1996

Described by the New York Times as “One of the most important design innovations of the 1990s”, Kyle Cooper’s groundbreaking title sequence is one of Se7en‘s most-imitated and influential elements. The fritzing, fuzzy graphics, distinct typography, and textual clues set over a remix of Nine Inch Nails’ Closer effectively establish the mood.

The titles don’t appear right at the top of the movie, but a few minutes in, after grizzled Somerset has met, and clashed with the over-eager new boy Mills. We have our cops, our city location, our seven day ticking clock, all we need is our killer. Somerset, unsatisfied by the sordid domestic murder suicide scene he just visited, also needs something more. A high note to go out on. A legacy. He sits on his bed, sets the comforting clack of his noise-blocking metronome, and drifts off to sleep. Some fan theories suggest that everything which follows is his dream. If so, the fragmentary images of the title sequence represent the liminal phase of dreaming, as the subconscious whirls, flickers, flails before settling into a nightmare track.

Se7en‘s title sequence plunges us inside an obsessive mind, giving us close up details of paper (how porous!), medical illustrations, negatives, text, photographs, newsprint cuttings, money. These raw materials are chopped and repurposed, stuck into a notebook along with pages and pages of handwriting. It’s the work of an unseen man who also uses a razorblade to slice at his grubby fingers. The details (the word “pregnant” crossed out, photographs of head wounds) are meaningless as they flicker across the screen, but will become portentous as the narrative progresses. Cooper says he wanted to communicate the sense that Doe was “super super evil.” Indeed, the sequence conveys exactly that, which is all we need to know about Doe until he finally makes his appearance in the third act.

- Anatomy of An Opening Sequence: David Fincher’s Se7en by Phil De Semlyen (Empire Online, October 15, 2010)

- The New Look In Film Titles: Edgy Type That’s on the Move by Laurie Halpern Benenson, New York Times, March 24, 1996

- Stars Aligned for Se7en’s Main Title – Watch The Titles

- Murder by Imitation: The Influence of Se7en’s Title Sequence by Tim Groves (Screening the Past)

Aesthetic

- Seven: Sins of A Serial Killer – David E. Williams in American Cinematographer, June 01, 2017

Iterations

Se7en is a startlingly original screenplay and has – thus far – remained resistant to sequilitis. However, in 2007 Senescope Entertainment published a glossy graphic novel series based on Doe’s origin story.

Further Reading

- The Parable of the Madmen: Examining the Moral Mad Figure in ‘Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory,’ ‘Se7en,’ and ‘Saw’– Veronica McDonald (Owlcation)

- Bleak chic by Benjamin Svetkey in Entertainment Weekly, November 3, 1995