1980s Horror – Carnival Row

Horror movies of the 1980s (which probably begin in 1979 with Alien) exist at the glorious watershed when special visual effects finally catch up with the gory imaginings of horror fans and movie makers. Technical advances in special effects (animatronics, liquid and foam latex) meant the human frame could be distorted to grotesque new dimensions on screen.

This coincided with the decadent and materialistic aesthetic of the 1980s. Having it all was important. Showing it off was paramount. It was truly the Age of Excess. People demanded tangible tokens of material success – bigger, shinier, faster, with more knobs on – as verification of their own value in society.

In the same way, 1980s horror movies delivered the full colour close-up, look-no-strings-attached, special effect in a way that previous practitioners of the art could only dream about. Everything lurking in the shadows in older horror movies was now dragged into the garish light of day. The monsters were finally out of the closet.

Once they were exposed to the light, however, these monsters proved to be the same as ever: ghosts (of supernatural origin), werebeings (of human origin), and slimy things (origin unknown). The latter maintained a strong presence in 1980s horror movies; the cuddly aliens represented in Star Wars and ET were counterbalanced by the grotesque extraterrestrials of the Alien franchise and The Thing.

Werewolves made a strong showing in early 1980s horror with the Howling series and An American Werewolf in London – and perhaps, as in the 1940s, reflected a fear of the ‘wolves’ stalking each other under the aegis of the Cold War. Ghosts were not so numerous but still provided cause for terror, whether they were traditional ones, such as those haunting the Overlook Hotel in The Shining (1980), or of more ambiguous status: Freddy Krueger is technically a ghost.

The Shining (1980)

Although it’s based on Stephen King’s 1977 bestseller about a haunted hotel, Stanley Kubrick’s movie differs substantially to the book. Rather than being about a family, it’s about a location. The Overlook, as imagined by Kubrick, is a series of nightmare-inducing spaces that simultaneously cause claustrophobia and agoraphobia. Kubrick eschews King’s supernatural explanation that the hotel is an evil entity which manifests via a spectral corpse in the bathtub or topiary creatures that come to life. Instead he suggests it’s an extreme case of sick building syndrome: something rotten in the architecture and the patterns in the carpet burrows into Jack’s brain and sends him over the edge.

Read More About THE SHINING>>>>>>>

Zombies made a comeback, from the slick satire on shopping mall frequenters, Dawn of The Dead (1979), to the inspired gore-fest Brain Dead (1990) successfully lurching across the screens in various stages of decomposition.

Horror generated good box office business in the 1980s, so much so that there are a couple of big-budget family-orientated entries to the genre – deliberately restrained to earn a PG-13 rating. Joe Dante began by directing low-budget horror fare such as The Howling, and graduated to the major league with Gremlins (1984) a film aimed squarely at the Christmas family market, but containing some highly vicious little monsters and some very gory special effects. Of course, kids loved it, as they also loved Ghostbusters (1984). These movies were big hits ($148M and $291M at the box office respectively).

As in the 1950s, 1980s horror movies tended to be tilted towards 15-24 year old males; an audience seeking thrills as a rite-of-passage, wanting to prove to their peers they could tolerate whatever grossness filmmakers could throw at them. The old ARKOF formula held true.

Inevitably, most of these movies were made by men. Sex and nudity were casual, another aspect of the thrills on offer. Women’s bodies, in the form of (usually youthful, white and blonde) cheerleaders, sorority sisters, babysitters, girlfriends and stepmoms continued to be presented as objects – to be slathered in gore and slavered over by monsters and male audience members alike. There was no place for the female gaze in a lot of 1980s horror movies – thankfully those days are gone. Nonetheless, revisiting former favorites from this era can be a problematic pleasure.

Inside Out: Body Horror

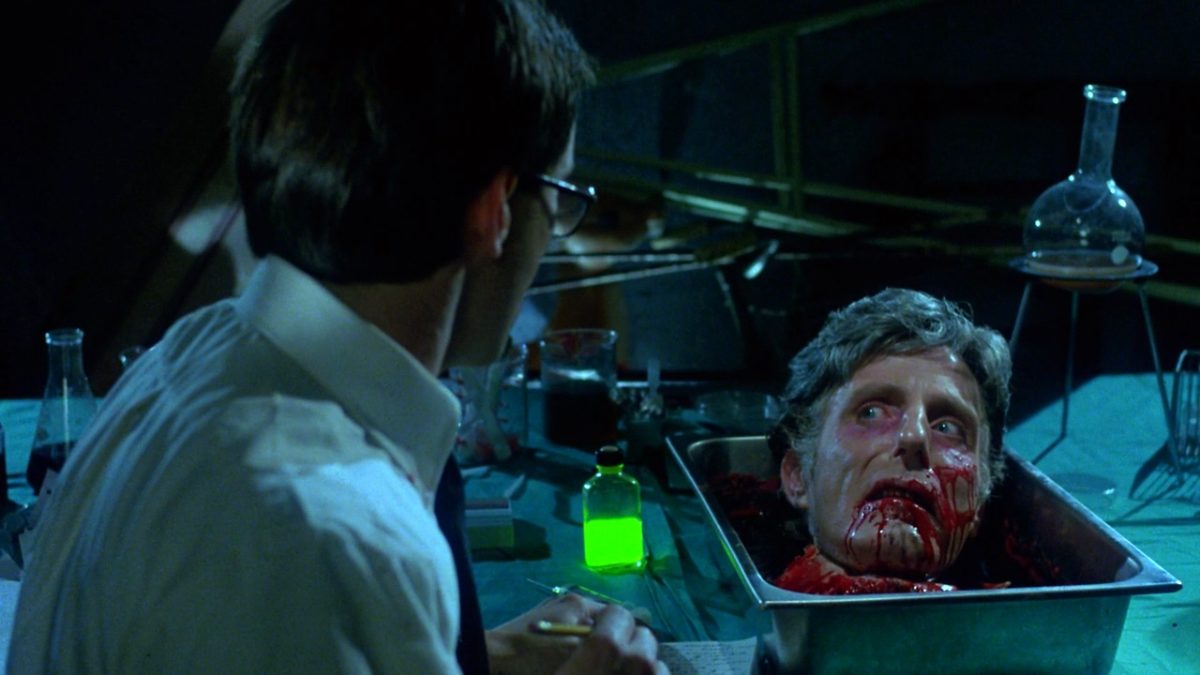

Horror films have always dealt with the taboos surrounding Death, and in the 1980s they began to deal with evisceration, pulling apart the human body and turning it inside out, with all its slimy viscera on display. As the tagline for Re-Animator (1985) intoned,”Death Is Just The Beginning”, and viewers of 1980s horror films get shown many of the processes which occur peri and post mortem. Special effects creators fell over each other to create sequences that had never been attempted on film before. There would be no more monsters with zippers up their backs. Instead, the focus was on unzipping abdomens and torsos, spilling their contents onto the floor.

Over previous decades, movies managed to terrify their audiences through subtle suggestion: if you can trigger someone’s imagination, they’ll scare themselves. 1980s horror movies tended to take the opposite approach, presenting grotesque images to induce a physical reaction of nausea and fear, challenging the audience to keep watching despite their revulsion. Very little was left to the imagination.

To a certain extent, this worked. It’s natural to feel revolted by images of body parts, even if they’re made from rubber and latex. Humans have evolved to feel disgust at such things: it’s a protective reaction that keeps us from getting too close to potentially toxic, infectious, or otherwise dangerous substances.

However, the cumulative effect of repulsive images is one of desensitization; experience too many and they lose their meaning, and their power to shock. Each new wave of monstrosity makes the previous one seem tame. Consequently, by the end of the decade, the latex lunacy tilts more towards the slapstick than the horrific. Reanimated body parts whiz around the screen as a gag, not a scare.

Brian Yuzna was the king of this type of quasi-comic schlock, and his riotous riffs on the stories of H.P. Lovecraft, Reanimator, Bride of Reanimator, From Beyond (1986) and Society (1989) are all classic “should-I-laugh-should-I vomit?” cases in point.

Other 1980s body horror took itself more seriously: most notably David Cronenberg’s Videodrome and The Fly. He was an early adopter of Body Horror during the 1970s, as Shivers, Rabid and The Brood all display a morbid fascination with human biology, albeit with a focus on the gynecological.

Videodrome (1983)

In his first big studio feature (for Universal), David Cronenberg uses body horror as a sharp tool to poke at the media landscape of the early 1980s. Thanks to a trio of recent technological developments (cable TV, the videocassette recorder, the remote control), it was now possible for the hooked-up viewer to spend literally hours of each day hopping from TV channel to TV channel, watching a few seconds before moving on in search of more enthralling entertainment. This rendered the TV viewer more passive, more compliant than ever before. No need to focus, or follow a thought, just sit back, slack-jawed while random images unfurl themselves straight into your brain.

Once you surfed past the big names (HBO, CNN, ESPN etc) cable TV became a patchwork of local and niche stations, broadcasting at odd times of day often from territories that lay outside the usual regulatory frameworks. That meant sex and violence – at the outer limits of shareable human experience. Videodrome centers on Max Renn (James Woods), head of one such fringe TV channel, CIVIC-TV in Toronto. He’s bored by the soggy porn and ketchup trauma of the current line-up and is on the hunt for something new. He finds it in ‘Videodrome’, when he catches an illicit transmission of what looks like authentic torture and murder from somewhere in (supposedly) Malaysia. Renn is hooked, instantly, on the graphic images that give him the warm buzz in his hypothalamus he’s been yearning for. He vows to sign the show to his roster.

Renn’s search for the origins of Videodrome leads him down a psychosexual rabbit hole. He begins hallucinating that his body is transforming in response to viewing the show: a giant, yonic hole appears in his torso, turning him into a human VCR. No longer a passive viewer, he’s fusing with the technology, letting the signal take control. Human flesh, having been a constant for millennia, is evolving to the next level (a concept also explored in the Tetsuo trilogy, beginning in 1989).

The Fly (1986)

Videodrome was a financial flop, but that didn’t prevent Cronenberg being handed the reins for Fox’s remake of 1958 Vincent Price-starrer, The Fly. In this version, the scientist’s transformation from human to insect is gradual rather than immediate, giving him time to appreciate the full horror of his situation rather than just having to deal with it. This also gives Cronenberg the opportunity to explore his ur-narrative, Mad Science, from another angle.

Seth Brundle (Jeff Goldblum) is a goofy, over-enthusiastic young scientist who thinks he can impress a girl, Ronnie Quaife (Geena Davis) with his teleportation machine. Although he doesn’t realize it immediately, his demonstration goes horribly wrong, fusing his DNA with that of a stray housefly.

Seth’s metamorphosis into Brundlefly serves as a meditation on aging, disease, and the transience of flesh. This is the body horror that affects us all. While his decay has been read by many as a metaphor for AIDS, which was rampant at the time, Cronenberg denies this, describing the transition as “more fundamental”:

in an artificially accelerated manner, he was aging. He was a consciousness that was aware that it was a body that was mortal, and with acute awareness and humor participated in that inevitable transformation that all of us face, if only we live long enough.

The Beetle and The Fly by David Cronenberg

Initially, Seth benefits from a Peter Parker-esque insect surge: the nerd becomes confident, libidinous, gymnastic, even. However, this rejuvenation is brief. As his cells replicate, the insect DNA destroys the mammal, sloughing off his hair and teeth, skewing his skeletal structure and digestive system to its own design. Chris Walas created the Oscar-winning special effects around seven distinct stages of Seth’s journey from a man with a rash to a pustulating mass of flesh (once again) fused with a machine.

The Thing (1982)

Overlooked on its release but now hailed as a classic, John Carpenter’s definitive take on body horror is another remake. He took the Howard Hawks’ 1951 sci-fi thriller (based on a short story by pulp author John W Campbell called Who Goes There?) The Thing From Another World and turned it into a gorefest that has never been equalled.

Retrospectively, The Thing has proved itself to be one of the most important horror movies of the 1980s, despite not being a box office success at the time. It is now seen by many as visionary, from a technical (the special effects far outstripped anything previously seen and certain scenes are horrifying to watch even today, nearly three decades on), and from a philosophical perspective. Like Invasion of the Body Snatchers it offers a discourse on what it is that makes us human, by examining what happens when our humanity is engulfed by alien biology.

Read more about THE THING>>>>>>>

Video Nasties

1980s horror movies benefited immensely from the introduction of home video. The VCR made movie watching a private activity for the first time in the medium’s history, conducted in the home rather than in a regulated public theatre. What people wanted, of course, was pornography, lots of it. But they had a similar appetite for horror, which also delivered a physical thrill, on a more socially acceptable basis.

Direct-to-video horror movies were produced on the same basis as the AIP titles of the 1950s; a grotesque title, a gory tagline and a gruesome cover were all that was needed to get a video store-browsing customer to pick up the box and say “this one looks good”. Usually budgeted at between $250,000 and $2 million, and clocking in at an average of 80 minutes these movies represented more variations on the slasher theme, or constituted loose sequels to a title that had already been successful as a theatrical release.

As the marketing was all about promising “killings”, aimed at a niche audience, there was no need to employ stars (although you might find a couple of A-listers on their way up the ladder). The Drive-In had finally come home, allowing teenagers to consume horror movies in a private space (the basement or the bedroom), without any adult interference, without any interference at all, if desired.

Think of the Children

Anyone who was a teenager in the 1980s will remember discussing horror movies not in terms of plot, or performance, or production values, but in terms of “grossness”, the all important G-factor. The best movies had the grossest moments. This was evaluated by the effective combination of shock and excess, full technicolour representations of penetration, decapitation, amputation, and of course, implosion and explosion of body parts. Notorious releases from the 1970s, once relegated to the most late-night, sleaziest theaters on the grindhouse circuit (if anyone watched them at all) were re-released to delight this new market. Distributors took out full page ads on the backs of magazines highlighting mutilation and murder.

These movies were available to view, repeatedly, by anyone with access to a VCR and the tape. This was also the era of the Generation X latchkey kid, left to their own devices for a couple of hours after school. They bypassed any kind of parentally enforced ratings system or official censorship. If a film had been theatrically released, in theory it carried its rating forward to video release. However, video shop proprietors ignored the law in favor of rental income and handed out tapes like candy. Straight-to-video shockfests went largely unrated. Thus, a generation of children were exposed to eye-gouging, fingernail-pulling, cannibal feasts, exploding heads and tree rape.

Legal Measures

In the UK this led to the notorious “Video Nasty Debate”, as the tabloid press screamed with headlines of the “Sick Films Warping A Nation’s Young Minds” variety. The film makers would not, or could not clean up their act; they were supplying violence and gore to an adult market that was lapping it up voraciously. The Evil Dead was cut by a hefty 49 seconds for both theatrical and video release in the UK, and was withdrawn after a series of high profile court cases, in which it was argued that the film was obscene. It was probably singled out for attention because it was the top rental in the UK at the time.

The result of legal action against the distributors of the “video nasties” (39 titles eventually made the list) was a law passed to regulate the sale and distribution of video in the UK (The 1984 Video Recordings Act). This was the first time a UK government had passed a new censorship mandate since 1737, and was seen as a triumph for the moral majority. Their victory was rather hollow as it only served to send the trade underground. These titles were available in the USA, plus any self-respecting teenager could tell you which of their local video emporiums continued to provide under-the-counter “banned” videos.

From our perspective, four decades on, when every teen has free access to all kinds of horrendous media via their smartphone, it’s difficult to see what all the fuss was about.

- British Board of Film Classification (equivalent of the MPAA) Case Study on The Evil Dead – the censors’ point of view

- Video Nasties – a clear account of the situation

- Let There Be Blood – 2002 Guardian article on the pre-VRA bloodbath

- The Video Nasties Furore – detailed discussion

A documentary, Video Nasties: Moral Panic Censorship and Videotape (2010) deals with the era in more detail.

The Evil Dead (1981)

Most of the 1980s video nasties have faded into oblivion, with one notable exception, The Evil Dead. Made on a shoestring budget by three guys barely out of their teens, it attracted worldwide notoriety for an extraordinarily graphic rape scene. It was banned outright in many countries and slashed by censors in others. Despite this (or because of it, oh misogyny!) The Evil Dead became a cult favorite, spawning sequels, a remake and a TV show.

Read More About THE EVIL DEAD>>>>>>>

One Is Never Enough: Sequelitis

Moviemaking is a business, a notoriously unpredictable, crowded, and expensive business in which financial hits are few and far between, barely making up for eye-watering losses. It would be fiscal madness, if a movie sells, not to keep selling it, or as many versions of the original as you can get into the production pipeline. Audiences are already familiar with the characters and scenarios, stars can reprise roles, everyone knows what to expect so the marketing is straightforward. So, sequels have been an essential component of the movie business since the beginning – George Méliès made a sequel to A Trip To The Moon, The Impossible Voyage in 1904.

Sequels aren’t necessarily a bad thing in and of themselves. However, as Universal discovered in their monstrous race to the bottom in the 1940s, too many, or poor quality sequels can destroy a beloved (and lucrative) franchise. Audiences grow tired of the same-old same-old, and the once-frightening can become comic through repetition and over exposure (and giving silent killers crappy one-liners).

Sequels can be terrible because filmmaking is an art as well as a business. A good horror movie is so much more than its raw components and it’s almost impossible to recreate the magic for a second go-around – even if you throw more money at it. Many original entries in long-running franchises are low-budget productions, featuring unknowns, but they express fresh ideas and inflict thrills with verve, thanks to the vision of the filmmakers. The sequels don’t always deliver to a similar depth or degree.

Irregardless, in keeping with the Greed Is Good ethos of the decade, movie producers went all-in on sequels to 1980s horror movies. Given the voracious appetite for both theatrical and home video releases – why not capitalize? The original creators and cast were often cut out of sequel deals. The production company owned the intellectual property and could rehash it as it they saw fit – as long as they felt the fans wanted it. And the fans did.

Home Is Where The Heart Is

Thanks to home video, fans were more familiar with their horror icons than ever before and the nature of the relationship was shifting. Whereas television and moviegoing offered a passive experience, the VCR offered limited interactivity (stop, freezeframe, fast forward, rewind, repeat view). Rented movies – and moments in those movies – could be endlessly replayed in the comfort of your home, alone or with friends. A movie was no longer a fleeting experience. As the decade progressed and videos became more available to buy, a videocassette was a collectible, a tangible object you could own and display, alongside any other related tchotchkes. Movie fandom was a badge, a t-shirt, a lunchbox, a baseball cap, a wearable cultural signifier, this is who I am. A movie was no longer just a memory or a dream: it sat on your shelf in your bedroom. In the materialistic 80s, it was a possession for others to judge you by. More = good. And more meant more of the same.

Not every 1980s horror movie that begat a sequel deserved one. Even the most notable franchises are patchy at best, with one or two stellar instalments outshining the duds. There are thirteen movies in the Puppet Master series (1989-2019), with one more on the way. Friday the Thirteenth (1980) has (to date) generated ten sequels, The Howling seven. However, the longer the sequels keep coming, and the closer to their originators they remain, the more fans learn to embrace the average, even terrible elements alongside the standouts. You don’t just love one member of the family, you welcome them all. And you keep the faith. Tangled rights issues notwithstanding, some movie series of the era are still spitting entries onto our screens today (hello, HALLOWEEN), and people who were there for the original show up in droves. It would be rude not to.

A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984)

Wes Craven, the former college professor responsible for two of the darkest and most deranged movies of the 1970s (Last House on The Left and The Hills Have Eyes) unveiled a brash, commercial franchise in 1984: A Nightmare on Elm Street. The monster, a hideously scarred Freddy (named after a kid who bullied Wes Craven at school) Krueger represents a successful blend of humour and horror, a deranged killer who doesn’t lurk silently behind a hockey mask but menaces in full view, spitting one-liners as he sharpens his trademark glove. In terms of Jungian archetypes he is the ultimate Shadow Trickster, the shape changer who relishes sick jokes. Freddy was a merchandising dream, an icon for a generation whose distinctive striped jersey, battered hat and scarred visage has shifted many t-shirts, board-games, coffee cups, lunch boxes and even snow globes.

Read more about A NIGHTMARE ON ELM ST>>>>>>>

Child’s Play (1988)

Another serial killer with a smart mouth and a not-so-snappy way of dressing appeared in 1988, launching another successful franchise. Child’s Play(1988) introduced horror audiences to Chucky, who, as well as drawing on the long tradition of malevolent dolls on page and screen, provided an interesting nexus between the monster children of the 1970s and the serial killers of the 1990s. The self-aware irony pre-empted the tone of the post-modern Wes Craven movies of the 1990s.

Read more about CHILD’S PLAY >>>>>>>

By the end of the 1980s, horror movies were dumbed down to attract their target audience, with body counts through the ceiling and little attention being paid to plot or emotional authenticity. A glut of sequels and copycats were released to sate the appetites of aficionados of the genre and no one else. It looked as though the genre might have gone into a permanent tailspin – sequel piled upon sequel, endlessly recycled plots, lower and lower box-office receipts leading to lower and lower budgets, and a loss of respectability which meant that respected writers, directors and actors shunned avoided the taint of horror projects. But horror movies had been here before, at the end of the 1940s, and once again the genre successfully managed to reanimate itself. Abandoning vials of luminous green serum, horror went back to basics, and refocused on the most basic of all evils, ‘man’s inhumanity to man’.

Further Reading

- Links between the Divorce Rate and 80s Horror movies – we always knew they were about broken families

- Men, Women and Chainsaws – extracts from Carol J Clover’s book

- Trencansky, Sarah. “Final Girls and Terrible Youth: Transgression in 1980’s Slasher Horror” Journal of popular Film & Television. (2001)

Also See: In Search of Darkness – The Definitive 80s Horror Doc (2019)