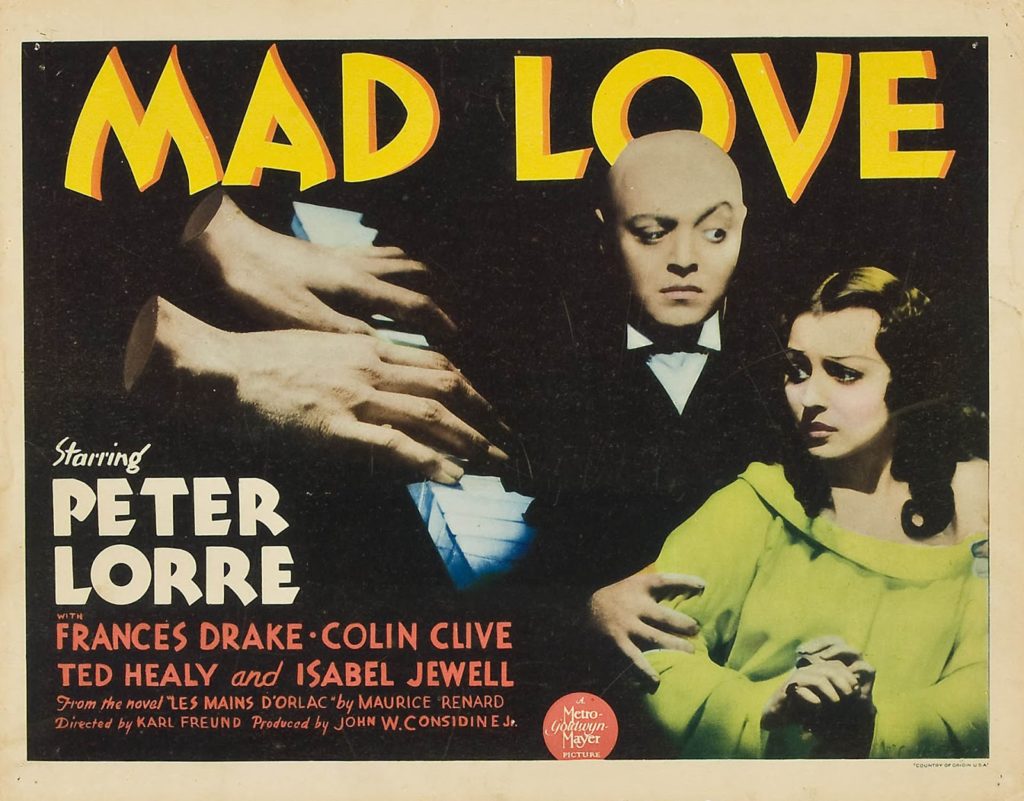

Mad Love is a twisted morality tale charting the rapid (68 minute) and irrevocable slide into madness of brilliant surgeon, Dr. Gogol, played by Peter Lorre with his signature blend of heavy-lidded menace and pathos, in his first American role.

“Mr. Lorre, with his gift for supplementing a remarkable physical appearance with his acute perception of the mechanics of insanity, cuts deeply into the darkness of the morbid brain. It is an affirmation of his talent that he always holds his audience to a strict and terrible belief in his madness.”

New York Times review of Mad Love, August 5, 1935

He was directed by another Austro-Hungarian immigrant, Karl Freund. Freund is best known for his work as a cinematographer on a wide variety of movies, from Metropolis to Murders in the Rue Morgue. By 1935, he’d already directed The Mummy (1933) for Universal, so he seemed like a safe pair of hands for this MGM project.

Visually – and unsurprisingly given Freund’s European resumé – Mad Love is expressionistic in tone. The action plays out against a series of dark diagonal lines that trap the main characters in corners, pinned by shadows and locked into their macabre ménage à trois. Freund, working with cinematographer Gregg Toland, lights Lorre as though he is a woman, with iconic results. Dr. Gogol glows like a screen goddess, perfectly smooth-skinned, his eyes haunted pools beneath his close shaven pate. Lorre harnesses the same dark glamor and wordless mystery as Garbo or Dietrich to convey the pain and complexity of his character.

Mad Love is based on the same Maurice Renard novel as The Hands of Orlac (1924), but centers on the hubris-and-fall of the hand-swapping surgeon, rather than the psychology of the mutilated piano player Stephen Orlac (Colin Clive). While Orlac becomes frantic as his hands seem to take on a life of their own, in this version the good doctor is the one who tumbles, cackling, over the sanity cliffs.

Dr. Gogol begins as a meek, somewhat pitiable figure, a stage door johnny with deep pockets, willing to squander all his francs on his object of desire. For 47 nights straight he sits in a private box at the theatre, enjoying the Grand Guignol-esque performance of Yvonne Orlac (Francis Drake) as the maiden tortured on a rack. When he finally screws up the courage to present himself in her dressing room, she rejects him, kind but brisk. Yes, she’s grateful he’s been funding her theater company for the past few weeks, but she’s about to retire from the stage and return to London with her husband. Gogol has to comfort himself with the purchase of the promotional wax figure of Yvonne that’s become surplus to the theater’s requirements.

After Gogol’s drunken, parrot-wielding housekeeper, Françoise (May Beatty) installs the wax figure in Gogol’s study, the narrative teeters on another path. Gogol has what he truly wants, the opportunity to gaze upon Yvonne in total privacy, without fear of rejection or disdain. The wax figure, frozen in open-mouthed supplication, is his to do with as he pleases. Any kind of sexual fetish was explicitly banned by the Production Code so, in the standard swerve around the censors, the dialogue takes the high road, glossing over any salacious inferences in the subtext. While Gogol waxes lyrical on the Pygmalion-Galatea myth in order to gild this new relationship as something worthy and high-minded, he has Françoise purchase a filmy, boudoir-ready negligée for the figure, just in case his non-verbal intentions haven’t been signalled clearly enough.

Although the modern sex doll as we know it wasn’t invented until the 1950s, statue love (as practised by Pygmalion) has been documented since ancient times. Men (and, more rarely, women) often prefer a silent, unresisting, inanimate object to unpredictable or unfaithful flesh and blood. Freund may have been inspired by news stories from his youth of a fellow Austro-Hungarian artist Oskar Kokoschka. In Vienna, in 1915, Kokoschka was so devastated by the end of his love affair with pianist and composer Alma Mahler he ordered a life-size doll made to look exactly like her. When it arrived, the replica didn’t quite function as he had hoped so, after painting it a couple of times he threw a party, ritually beheaded it, and buried it in his garden. Kokoschka wasn’t the only artist intrigued by replica women in this era. Around the time of Mad Love‘s release, man-doll love seemed to be having a moment. Man Ray and his fellow Surrealists were known for their use of disjointed female mannequins – and rumor had it the figures were used for private erotic play as well as public display. Over in Florida, real life mad lover/scientist, Carl Tanzler aka Count Von Cosel, was taking doll-love to the next level, slowly transforming his dearly departed Elena in her Key West tomb.

Increasing the ick factor, Drake appears as her own waxwork in many of the shots – like the actors in The Mystery of The Wax Museum two years earlier. This was a cheap and convenient way to make the mannequin look more lifelike on set, but the doubling, with feisty Yvonne muted as an acquiescent copy of herself, helpless to resist whatever advances Gogol chooses to make, creates disturbing undercurrents. We fear doppelgängers for good reasons: they cast no shadows and foretell death.

Gogol’s fixation on the waxwork is disturbing, but it might have remained harmless – a private peccadillo – if Yvonne and Stephen had left Paris as planned. Unfortunately for everyone involved, Destiny takes the wheel – a furious, vengeful Destiny, determined to punish all concerned.

Poor Stephen crushes his hands so badly in a train wreck that a double amputation is recommended – a cruel fate indeed for a concert pianist. His desperate wife refuses to accept this outcome and makes a deal with her personal devil, Gogol. Up until that point the good doctor hasn’t really done anything wrong. Indeed, he seems like quite a saintly type who performs intricate spinal surgery on children without demanding a fee. However, Yvonne’s pleading, coupled with the thought that she will become indebted to him, proves too much temptation. He steals the hands from a recently guillotined criminal and transplants them on to the end of Stephen’s arms. He gives back what God hath taken away.

This blasphemy is familiar territory for 1930s Mad Scientists, especially as the transplant operation is followed by a montage showcasing the latest in medical technology, including electrical coils, heat lamps, and ultraviolet light. The audience expects Gogol to be punished for his folly, and he is, his brilliant mind crumbling under the delusion that all he has to do to win Yvonne’s love is destroy her husband. His descent into madness is complete when he dons a bizarre, architectural costume and pretends to be Rollo, the handless and, until recently headless, executed prisoner, back from the dead. After that point, his death is inevitable – and a release.

Censorship

Unsurprisingly, the Hays office objected to several elements in the Mad Love screenplay. MGM was urged to be very cautious about depicting the trainwreck, and to avoid any unnecessary depiction of the injured. They were also advised not to show Gogol getting handsy with his waxwork. When the film was made, overseas censors objected to the guillotine, onstage torture, and strangulation scenes.

Reception

Mad Love worked well as a showcase for new star Peter Lorre – he was universally praised by critics – but the movie flopped at the box office. Like Freaks before it (another MGM “failure”), it exists within a moral grey zone, and was too weird and too sadistic to fly with contemporary audiences. Perhaps Orlac’s plight, injured and unable to work, reduced to selling off his possessions, also bit too deep for the Great Depression? Although the narrative takes place in a generic 30-years-in-the-past Mittel Europe, Orlac’s slide into poverty may not have appealed to audiences seeking escapist fantasy. It’s also tonally uneven, with the supposed comic relief of Francoise’s drunken rambling and Ted Healy’s annoying journalist, Reagan taking up too much screen time.

Over the years, Mad Love has become a cult classic. Lorre’s performance is timeless: Dr. Gogol has earned his place among the monster-victims of the 1930s. He’s another classic outsider, rejected because of his unconventional appearance and manner, despite the purity of his original intention. Lorre finds a flame of nobility in the odd little doctor and keeps it flickering until the end. Like Othello, he’s “one that lov’d not wisely but too well” and he must pay for his folly with his life. Yet, in keeping with the tone of the time, no matter how deserved (and inevitable, according to the constraints of the Code) his death is, the destruction of this monster is tragedy, not triumph.