![]()

Pre-Production

Like Dracula, the movie version of Frankenstein was based on a stage play (Peggy Webling’s Frankenstein: An Adventure in the Macabre) rather than on the original novel. Webling’s play was commissioned in 1928 by impresario Hamilton Deane, who had been very successful with his UK production of Dracula in the mid-1920s, and it proved to be a similar hit.

After the huge success of Dracula, released on Valentine’s Day 1931, Universal snapped up the screen rights to Frankenstein and the property entered the, even then, labyrinthine studio development process. Dracula screenwriter Garrett Ford hopped on board and drafted a screenplay based on two assumptions. First, that Frenchman Robert Florey would direct, and that Bela Lugosi would star in the leading role — as the mad scientist, Henry, not as his monstrous creation.

The Fort-Florey take on the story followed the arc of a man who would be a god and is punished for his sins. Thinking their movie would be a star vehicle for Lugosi, they gave the lion’s share of screen time to Henry and reduced the monster to a lumbering ogre without any lines. The studio had other ideas and insisted Lugosi would play the monster. This was a reasonable strategy, considering Lugosi’s infamously thick Hungarian accent. Lugosi himself was outraged at the idea that all he would be doing on screen was moaning and grunting so, after shooting some test footage in the monster’s makeup (which he hated), he rejected the part.

Jack Pierce, the makeup artist, had crossed Lugosi’s path before. Pierce was the chief of makeup for Universal and oversaw Dracula, where Lugosi insisted on applying his own makeup as the Count, as he’d done for the stage show. This must have been very frustrating for Pierce. His design for the Monster was much more complicated, but Lugosi still wanted to do his own face. The footage has been lost to history and there are competing accounts as to the botch job the actor made of it, but apparently the producer, Carl Laemmle Jr, “laughed like a hyena” when he saw the test.

With Lugosi refusing to play ball Florey was out too, much to his chagrin. His successor was the Englishman James Whale, a Carl Laemmle Jr. favorite who’d scored successes with two adaptations of wartime melodramas, Journey’s End (1930) and Waterloo Bridge (1931). Laemmle offered Whale any picture on the current Universal slate and, wanting to branch out from war stories, he picked Frankenstein. This began a classic four picture run (Frankenstein, The Old Dark House, The Invisible Man and The Bride of Frankenstein) with Universal that established Whale as a major genre influencer—as well as making the studio a lot of cash.

Legend has it that 43 year-old struggling character actor Boris Karloff (who, like Whale, was born in the UK) was plucked from obscurity in the studio canteen to play the Monster. It’s more likely that Karloff came to Whale’s attention after he played a murderer in a Los Angeles stage play, The Criminal Code. With his emaciated frame and lugubrious face, Karloff — who was a much more versatile actor than Lugosi — was the perfect pick for the part.

The Monster’s Makeup

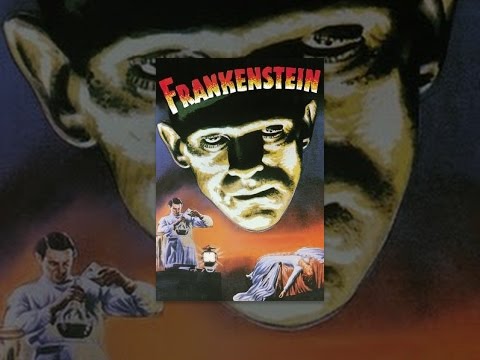

Jack Pierce’s grotesque, other-worldly makeup design for the Monster proved to be instantly iconic, creating a brand image for the character that’s still widely recognizable almost a century later.

Pierce reshaped Karloff’s skull using layers of cotton and collodion. He covered this with gray-green greasepaint, with purple shadows to create that ‘fresh from the grave’ look and clipped on staples and neck bolts. Karloff suggested adding a layer of wax to his eyelids to give that distinctive drooping look and removed a dental bridge from the left side of his mouth which resulted in a sunken cheek. The entire look took around 3½ hours to put on and two hours to take off.

When fully made up, and sporting his giant asphalt-spreader’s boots and too-small black suit, Karloff looked so terrifying that Laemmle insisted he wear a veil to walk to and from the set, lest he shock studio secretaries into spontaneous miscarriages.

Studio execs knew Karloff as the Monster was scary, but they really didn’t appreciate the power of his portrayal until after the movie hit theaters. They thought his character was so peripheral that he was listed in the credits as “?” and they did not even invite him to the premiere, yet it is his lumbering, pathetic, enduring creation (Karloff referred to the character as “that dear old man”) that’s now synonymous with the name ‘Frankenstein’.

Production

Shooting began on August 24, 1931, and wrapped on October 3 of that year, running around $30,000 over its allotted budget of $261,000.

While the Fort-Florey script remained structurally intact, final revisions came courtesy of John Russell, who was never formally credited, but who added the scene where Fritz drops the regular human brain intended for the Monster’s head and replaces it with a criminal reject. Significantly, this flourish downgrades Henry from an evil genius realizing his masterplan to a bumbling scientist unknowingly thwarted by his assistant’s ineptitude. This seems very in keeping with Whale’s sardonic sense of humor.

Eschewing most of the metaphysical musings of the original novel, the movie focuses on arrogant Henry(Colin Clive)’s desire to play God and create life. He rejects the normal trappings of life (including his beautiful fiancé Elizabeth, played by Waterloo Bridge star Mae Clarke), preferring to lurk in his castle laboratory experimenting at the intersection of electricity and human anatomy.

Loyal Elizabeth along with her former beau Victor (John Boles), Henry’s hunchback assistant Fritz (Dwight Frye), his former teacher Dr Waldman (Edward Van Sloan) are all on hand to witness the lever-pushing ‘birth’ of Henry’s new Adam. Henry delivers an ecstatic line at his moment of triumph —”Now I know what it feels like to be God!” — that even pre-Code censors considered blasphemous. This line was cut out of theatrical prints until quite recently.

Technician Kenneth Strickfaden made the sizzling laboratory set out of scavenged industrial pieces. He only loaned the various machines and gizmos to the studio for the movie and returned them to in his garage in Santa Monica when shooting was done — he then rented the pieces back to Universal for various sequels and spin-offs. By the time the set came up for sale in 2007 it had racked up credits in 60-70 movies. Current whereabouts: Unknown.

The Monster feels unwanted and unnatural from the get-go and turns killer, slaughtering Fritz and Waldman. In one of the most talked-about scenes of the movie, he then forms a brief connection with Little Maria (Marilyn Harris, aged 7), before accidentally drowning her and incurring the wrath of an entire village. For decades, the scene showing the actual drowning was cut out of prints of the movie as too shocking. Its omission left audiences wondering, however, about just what exactly happened to Maria in the moments before she died — as always, people imagine the worst possible scenario, and the restored prints actually seem tamer.

There was a lot of concern on set about how young Marilyn would respond to seeing her friend Boris in his Monster makeup for the first time. They needn’t have worried: she took his hand and asked if she could ride with him from the Universal lot to their location at Lake Sherwood, a 30+mile trip.

After Maria’s death (no one really misses Fritz or Waldman) the Monster is a fugitive. He shows up as an uninvited guest at Henry and Elizabeth’s wedding, where a flaming torches and pitchforks mob forms to hunt him down. The chase ends at a windmill: Henry is thrown off the top, and the angry villagers burn the structure down, presumably destroying the unnatural creature once and for all.

Whale originally shot a different, more final ending, showing the death of Henry at the Monster’s hands. The studio already had their eye on a sequel, however, so they ordered reshoots to make the main characters’ fates more ambiguous.

Reception

Opening just before Thanksgiving 1931, Frankenstein was a major hit, the must-see holiday movie and the box office champ of the year. Audiences struggling with the straitened circumstances of the Great Depression were able to escape their woes for the price of a movie ticket into a world of an ill-informed upstart God and his unhappy creation. The pathetic, beleaguered Monster struck a chord far and wide. Letters poured in for Karloff at Universal, all expressing sympathy for the Monster, and offering “help and friendship”. Ever the gentleman, he described it as “one of the most moving experiences of my life.”

Critics were generally positive, although some carped at the creakiness of the recycled sets, pointing out the sagging, wrinkled cyclorama that can be seen in some scenes, or mocking the “papier-mache mountains”. Others, more thoughtfully, commented on the underlying racism.

G.A. Atkinson, critic for British publication Era, wrote in 1932:

The narrative degenerates through rapid stages into a brutal and debasing man-hunt, ending with the incineration of the monster in a windmill, almost as if it were a Georgia lynching, which, in fact, the chase strongly resembles. The parallel may be unkind, but it is irresistible.″

Lynchings were common cultural currency across the United States during the twentieth century boom years of the Klan, which only began to fade away in the mid-1920s. As with King Kong (1933), it’s hard not to see Frankenstein as allegorical, referencing and feeding into the dominant white narratives of the time. From that perspective, the Monster begins life as someone’s property, and, once he escapes, his savage, uneducated nature renders him unfit for civilized social discourse. He commits the greatest crime of all, killing an innocent white girl, and must be hunted to his death by a mob of vengeful citizens.

Again, like King Kong, Frankenstein demonstrates a certain pity and compassion for its unjustly treated creature, but it doesn’t go far enough. The tide was turning, slowly but surely, against lynchings, with perpetrators brought to trial — although they were usually acquitted. Nonetheless, lynching imagery underlies what was accepted as family entertainment, with the Monster’s tortuous death played as spectacle to delight the righteous and bloodthirsty, crowd.

Further Reading

- FilmSite.Org – another exhaustive review

- Overview from CSIE @ NTU

- Frankenstein’s Castle – the definitive Frankenstein site gives a comprehensive overview of the whole Universal series of Frankenstein pics (includes info on The Bride of Frankenstein).