Carnival of Souls is a low-budget gem, a cult horror film that retains its power to haunt the viewer almost sixty years after it was first released.

Carnival of Souls was directed by Herk Harvey, a film-maker with several “industrial documentaries” (i.e. training films) under his belt, but no other fiction features. Shot in Lawrence, Kansas (at, and using the crew from the industrial film company, Centron) and around the abandoned Saltair amusement park in Utah for a supposed $33,000, the film is long on atmosphere and short on warm human relationships. From the opening drag race (which could in itself be a PSA warning teens against this dangerous activity titled “The Chicken Run Straight To Hell” ) to the muddy finale, every frame is pervaded with a sense of isolation and dissonance.

The screenplay, by John Clifford and Henk Harvey, draws on Ambrose Bierce’s civil war short story, An Occurrence At Owl Creek Bridge – as would Jacob’s Ladder (1990).

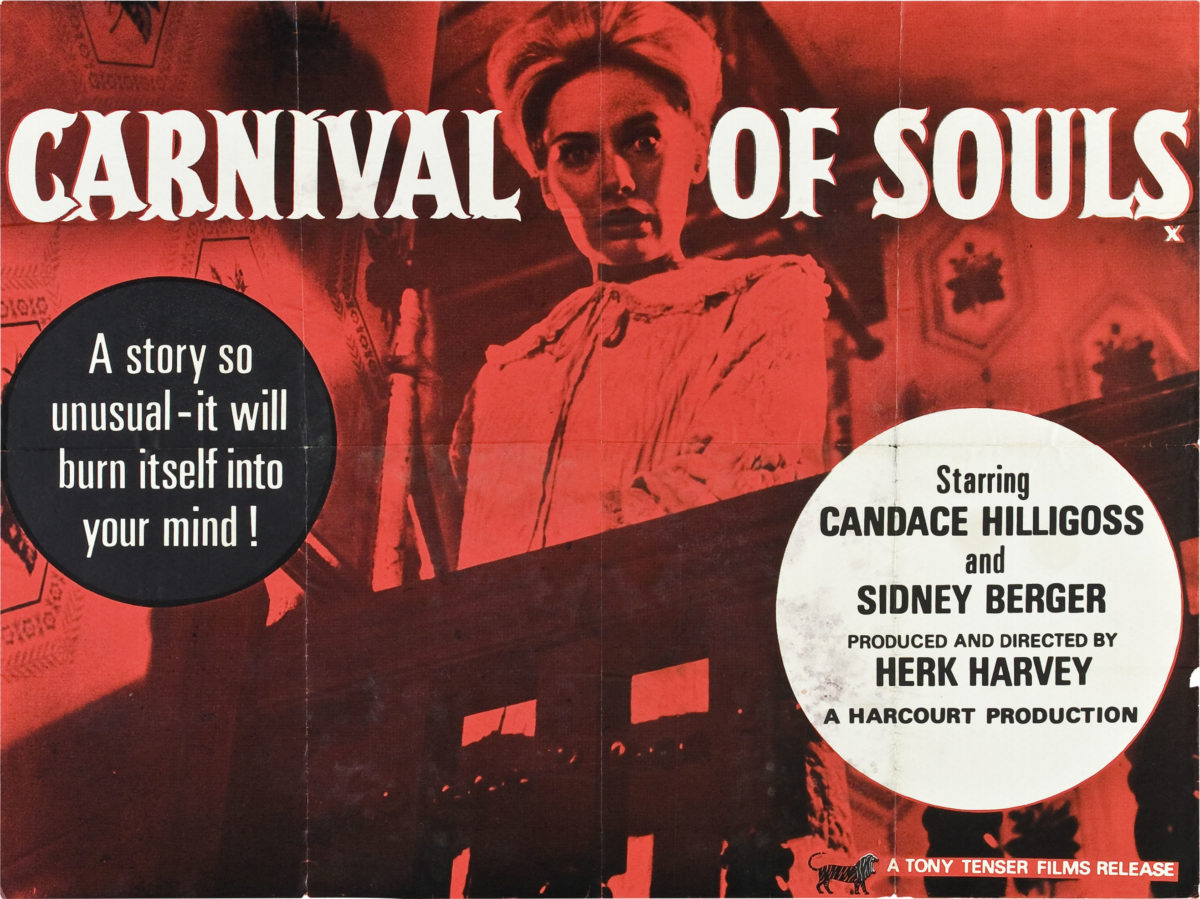

Candace Hilligoss (described by Roger Ebert as “one of those worried blonds like Janet Leigh”) plays Mary Henry, church organist and only survivor of the car crash that opens the movie. From the moment she crawls from the river, an inexplicable survivor, she is dazed and disconnected from reality. Now, she might be tagged as suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder but that diagnosis was not available in 1962.

She doesn’t seem to care about anything, from visiting her parents on the way to her new job in Utah, or the spiritual responsibilities of being a church musician once she gets there (“It’s just a job…I’m not taking the vows, I’m only going to play the organ.”). The only things that rattle her unconcern are the apparitions which follow her: ghoulish, hollow-eyed humans in dirty clothes (echoed six years later by Romero’s zombies in Night of the Living Dead).

One, in particular, appears in her car window as she’s driving, in the stairwell at her boarding house and at the auto shop. He seems intent on luring her out to the abandoned pavilion, a structure which fascinates her, notwithstanding the specific warnings of her boss, the vicar. Ultimately, she answers the call of the undead.

En route, she has several strange episodes, where the people around her suddenly disengage totally from her world: she cannot be seen or heard (even by a burly motorcycle cop), despite her frantic pleas for acknowledgment and help. It’s as though she doesn’t exist in their sphere, the only ones who can see her are the ghouls, a bus full of them, who reach for her with open arms. Desperate for some semblance of human connection, she endures a date from Hell with alcoholic, lecherous fellow lodger John Linden (Sidney Berger). He practically humps the doorframe at their first encounter, and tries to pour whiskey in her morning coffee — he’s no dream lover. But even his salacious attentions are better than being left alone with the apparitions: when she finally kicks him out of her bedroom she seals her doom by severing her last human connection.

The final kicker, which might seem predictable today, offers a bluntly supernatural explanation for Mary’s fugue state, but 1962 audiences, familiar with loved ones returning from war, might have recognized the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder without being able to give them a name.

Carnival of Souls is an eerie experience, one that resonates long after the final frame has faded. The organ music (Mary plays, hears it on the radio) and absence of dialogue give long sequences the rhythms of a silent movie, and it is sometimes startling to hear diegetic sound (including human voices) return. The special effects are minimal, but the atmosphere is palpable: Harvey makes admirable use of the Saltair location, with the pavilion continually glowering on Mary’s near-horizon so that it’s impossible for her to escape. The ghouls, a combination of simple makeup and old clothes, are nightmarish, especially in the speeded-up sequences (is this the first use of fast zombies, predating 28 Days Later by forty years?).

Carnival of Souls was restored and re-released on Blu-ray by the Criterion Collection in 2016. Very much worth your time.