During the 1930s, movies with supernatural, violent, science fiction or fantasy elements became a target for literal-minded censors, who were concerned that the masses might believe or, still worse, imitate the horrors they witnessed on the silver screen.

‘H’ Is For Horror

The British Board of Film Censors (BBFC – later the C came to stand for Classification) was established in 1912 to standardize film ratings across the UK. Local councils decided what could or could not be shown in their town and needed a national rating system rather than making ad hoc decisions. They rated films as either ‘U’ (suitable for all) or ‘A’ (more adult content although children weren’t officially banned). The BBFC had the power to cut scenes they felt would be offensive, present a moral danger, or generate political controversy (such as by insulting royalty or jeopardizing the war effort).¹

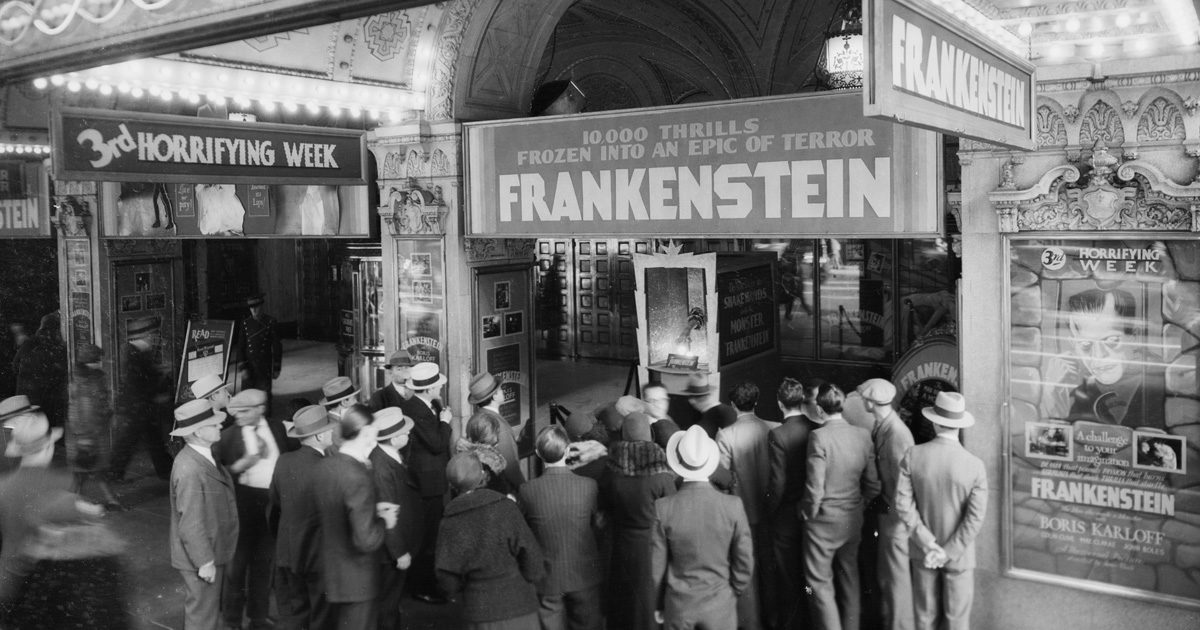

In 1932 the BBFC introduced the ‘H’ for Horrific advisory certificate, classifying the movie as unsuitable for those aged under sixteen. This was a direct response to Universal’s Frankenstein (1931), banned by London County Council and Manchester City Council (even after the BBFC had cut the scene in which the monster kills a little girl). Even though only four films received this classification in 1934, and six in the first half of 1935 when Edward Shortt, (then President of the BBFC), delivered a speech titled ‘The Problems of Censorship’ to the Cinematograph Exhibitors Association, he commented on the “tendency towards an increase in the number of films which come within the ‘horror’ classification, which I think is unfortunate and undesirable”². He further reflected on his concerns about the horror movies arriving from across the Atlantic.

“I cannot believe such films are wholesome, pandering as they do to the love of the morbid and horrible… Although there is little chance of children seeing these films, I believe they will have a deleterious effect on the adolescent. I hope that producers and renters will accept this word of warning and discourage this type of subject as much as possible.”³

From this point onwards, local councils took to banning movies that had been classified as ‘horrifics’, including those we now consider classics, such as Bride of Frankenstein. As a result, exhibitors were reluctant to book prints as they might not be able to screen them as advertised – the councils had a nasty habit of waiting until the last minute to announce their ban. This effectively closed off much of the British theatre circuit to horror films until after the Second World War.

¹ https://www.bbfc.co.uk/education-resources/student-guide/bbfc-history/1912-1949

² https://www.bbfc.co.uk/education-resources/education-news/blast-past

3 Censored Screams: The British Ban on Hollywood Horror in the Thirties by Tom Johnson (McFarland, 1997) p121

The Production (Hays) Code

Throughout the 1920s, Hollywood both in front of and behind the screen was fuelled by a series of salacious scandals: adultery, drugs, alcohol, murder, rape, homosexuality — you name it. Audiences lapped up the gossip about stars as eagerly as they consumed saucy silent movies featuring nearly-nude actors, debauched love triangles, and heinous crimes, for which the perpetrators weren’t always punished. The moral guardians of the nation — led by the Catholic Church — were outraged, firstly that this level of decadence was considered entertainment, and secondly that it was so freely available to the masses.

Then, as now, a moral panic bubbled about the connection between the depravity shown onscreen and what audiences thought, said and did after they left the theater. There was no consistently applied form of censorship: censors at a city and state level could request cuts on a by film basis, but that didn’t stop the unedited print being shown elsewhere, often marketed with a “Banned in ______” tagline. The nation’s moral arbiters agreed that something should be done.

The studios resisted the idea of government censorship, preferring to go down the path of voluntary self-regulation. Will Hays, a former Postmaster General and savvy Republican politician, was invited to be President of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America from its inception in 1922. This organization was founded in the wake of the Fatty Arbuckle/Virginia Rappe scandal when it became obvious Hollywood needed to get its house in order. Hays was tasked with writing a ‘Production Code’, laying out the standards of decency to which all Hollywood producers would voluntarily adhere.

It took him eight years (the introduction of talkies in 1927 complicated matters somewhat), but Hays formally unveiled his Code on March 31, 1930. It was written by a Jesuit priest (Father Daniel Lord) and the devout Roman Catholic editor of the Motion Picture Herald, Martin Quigley. It’s a fascinating document, driven by some very noble thinking about the power of motion pictures to elevate culture, nurture the young, smash vicious stereotypes and communicate shared social values. It also, predictably for its time, sets very narrow moral standards based on white Catholic heteronormativity.

Initially, the producers who pledged to abide by Hays’ high-minded list of Do’s, Don’ts, and Be Carefuls ignored it. They dutifully sent screenplays over to the Hays office to get the stamp of approval, but then either shrugged off comments or snuck in rewrites before shooting. For the next four years, an era now known as ‘Pre-Code‘, they rode roughshod over Hays’ limits. Nothing sold quite like salacious, so they kept crossing the line.

On the other side, the moral arbiters who had been promised change were very unhappy, particularly when they felt that the ideas espoused in Saturday trips to the movie theater undermined or even directly contradicted what was preached from the pulpit the following morning. Then, as now, they felt threatened by diversity and anyone who didn’t look, speak or worship like them. The Methodist magazine Churchman railed against the “shrewd Hebrews who make the big money by selling crime and shame.” The Catholic Church formed the Legion of Decency and, by 1934 was threatening a wholesale boycott of indecent movies.

The prospect of taking a major financial hit made the studios concede. Hays hired another staunch Catholic, former journalist Joseph Breen as his content watchdog and, from July 1934, the Production Code was enforced in earnest.

From July 1, onwards, any movie produced by a Hollywood studio had to have a certificate of approval from the Production Code Administration, it could not be released – and could not make any money. Moreover, Any picture shown without the Hays office seal of approval was slapped with a $25,000 fine.The authors of the Code wanted motion pictures to rebuild “the bodies and souls of human beings” and had newly beefed-up powers to enforce their rules. This meant forcing genre filmmakers to turn away from the dark side they’d so recently relished – the monstrous, maverick, and malevolent aspects of humanity. In the Underlying Principles of the Production Code, the anti-horror sentiment is spelled out quite clearly.

- No picture shall be produced which will lower the moral standards of those who see it. Hence the sympathy of the audience should never be thrown to the side of crime, wrongdoing, evil or sin.

- Correct standards of life shall be presented on the screen, subject only to necessary dramatic contrasts.

- Law, natural or human, should not be ridiculed, nor shall sympathy be created for its violation.

The Code went on to list the specific acts that were prohibited on screen, including

- Murder (particularly revenge killings)

- Seduction or rape

- White Slavery

- Miscegenation

- Disrespect of Religion

- Surgical Operations

- Apparent Cruelty to Children or Animals

As the Production Code limits bit, the maudlin monsters, flirtatious giant apes, exotic tribespeople, LGBTQ-leaning characters, or God Complex-driven scientists that had made Pre-Code horror movies so rich and challenging faded away. By emphasizing the “correct standards of life”, and “Law, natural or human”, the censors were pushing back against non-religious exploration of the supernatural – or any attempt to frame Bible stories as spook tales, despite their ghostly or miraculous elements. As the world first tipped into populism then marched to war, they also wanted to quash any sympathetic portraits of the Other, which by Hays Code standards included any unmarried, non-heterosexual, non-Christian, non-white individuals.

The Code also sought to regulate the dissemination of modern scientific thinking by keeping medical and ethnographic imagery out of the cinema. The Scopes Trial of 1925 demonstrated how much the religious establishment resisted the teaching of evolution and was wary of science in general. Daniel A. Lord, the Jesuit priest who was one of the architects of the Code, emphatically rejected Darwinism, which he described as “the vicious attack of the immoralists which began when science decided that men and women were merely animals from whom only animal morals could be expected”4. He and his cohort believed modern science was a threat to Christian civilization and that it needed to be contained. Eradicating medical activities such as surgical operations from the screen was the next step after banning textbooks in schools.

4. Daniel A. Lord’s autobiography Played By Ear (1956) pp274-275

Further Reading

- British Board of Film Classification: Student Guide

- Censored Screams: The British Ban on Hollywood Horror in the Thirties by Tom Johnson (McFarland, 1997)

- The Devil’s Advocate: Will Hays and the Campaign to Make Movies Respectable — Stephen Vaughn in the Indiana Magazine of History Volume 101, Issue 2, pp 125-152